(Acari: Erophyidae)

Pearleaf blister mite

Phytoptus pyri Pagenstecher

Appleleaf blister mite

Phytoptus mali (Burts)

The pearleaf blister mite was introduced from Europe, probably before 1900. It is currently a pest in most pear growing regions of the world. The appleleaf blister mite was first described in 1970 in Washington, although it may have been present in the Pacific Northwest as long as the pearleaf blister mite. Feeding by these mites causes blisters on leaves and fruit. Although at one time considered serious pests, they are now rare in commercial orchards of the Pacific Northwest.

Hosts

Pearleaf blister mite and appleleaf blister mite are pests of pear and apple, respectively, and possibly attack related plants such as mountain ash, cotoneaster, quince, serviceberry, snowberry and hawthorn.

Life stages

Egg

The egg is oval, pearly white and about 40 microns long.

Immatures

The first instar nymph is wedge-shaped, tapering toward the rear, and is about 70 microns long. It has two pairs of short legs near the front of the body. There are two nymphal stages before maturation with an inactive period before each molt. The inactive period at the end of the second nymphal stage is relatively long.

Adult

The female is 200 to 230 microns long and is light to amber yellow. It is cylindrical, tapered sharply at the posterior end, and resembles a short worm. It has two pairs of short legs near the front of the body. The male is about 150 microns long.

Life history

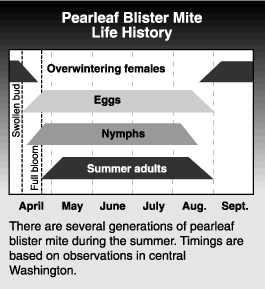

Blister mites overwinter as mature females at the base of buds or under outer bud scales. In spring, when buds begin to swell, overwintered females penetrate deeper into buds and lay eggs on live tissue. Development from egg to adult requires 20 to 30 days during the spring. Feeding of females and their offspring causes blisters on developing leaves. As the blisters form, leaf cells near the center of the blisters die and pull apart as surrounding cells enlarge, creating a hole. Mites of the first spring generation enter blisters through these holes and feed on soft leaf tissue inside.

Blister mites overwinter as mature females at the base of buds or under outer bud scales. In spring, when buds begin to swell, overwintered females penetrate deeper into buds and lay eggs on live tissue. Development from egg to adult requires 20 to 30 days during the spring. Feeding of females and their offspring causes blisters on developing leaves. As the blisters form, leaf cells near the center of the blisters die and pull apart as surrounding cells enlarge, creating a hole. Mites of the first spring generation enter blisters through these holes and feed on soft leaf tissue inside.

Several generations develop within blisters during a growing season. Summer generations require only 10 to 12 days to develop. When blisters become crowded or leaves become heavily damaged, mites may migrate to growing terminals where their feeding produces new blisters. Fruit damage is caused by injury to buds before bloom.

It is not known exactly how blister mite infestations spread from tree to tree or orchard to orchard. However, there is indication they can be carried by wind or by birds and insects.

Damage

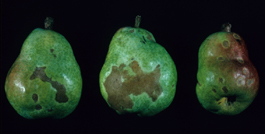

Blister mites attack both foliage and fruit, producing small galls or blisters. Blisters are green or red at first but turn light brown to black as affected tissue dies. Blisters vary in size, with the largest about 1/8 inch (3 mm) in diameter. Mites do not live in the blisters on fruit, but the fruit will be scarred.Severe infestations can deform apples. Damage to pears is less serious, but scarring can make the fruit unmarketable. Severe damage to foliage can cause leaf drop and reduce shoot growth.

Monitoring

A way to detect infestations before they reach damaging densities is to examine shoots in the tops of the trees after harvest using a 20- to 30-power lens to look for mites near or within dormant buds. However, this is time-consuming and blister mites are easier to detect on foliage during the growing season.

Check trees before bloom when infested young leaves will have noticeable light green to light red rough areas where mites have been feeding. These will be visible before leaves are completely unrolled. Infestations are even easier to detect later when blisters are clearly visible on fully developed leaves.

Biological control

Blister mites are not normally controlled by natural enemies. The predatory mite, Typhlodromus occidentalis, which can control spider mites on apples and pears, will also feed on blister mites when they are exposed. However, it cannot get into blisters.

Management

Orchards under good integrated pest management usually are not infested with blister mites. Blister mites often attack trees in abandoned or neglected orchards.

Blister mites have not developed resistance to pesticides, as spider mites have, and many effective chemicals are available. When treatment is necessary, choose a pesticide that is compatible with your pest management program. The best timing for chemical controls is after harvest when the mites migrate from leaf blisters to terminal and fruit buds. They are exposed in those sites until buds swell in the spring. Pre-bloom treatments can prevent fruit damage that occurs just before and during bloom.

Summer pesticide applications that have a fuming action or are systemic can give some control but are too late to prevent fruit damage. To evaluate the efficacy of sprays, check blisters for mite survival.