by Jay Brunner, originally published 1993. Updated 2019.

Pandemis leafroller Pandemis pyrusana Kearfott

Obliquebanded leafroller Choristoneura rosaceana (Harris)

Fruittree leafroller Archips argyrospilus (Walker)

European leafroller Archips rosanus (Linnaeus)

Several important tree fruit pests belong to the family of tortricid moths called leafrollers. Most are native North American insects that use several species of native plants as hosts, in addition to feeding on commercial tree fruits. The name leafroller comes from the larvae’s habit of rolling or tying leaves together when building feeding sites or shelters. The leafrollers most often found in mature apple orchards in Washington are pandemis leafroller and obliquebanded leafroller. Both have two generations a year. Although they feed primarily on foliage, fruit can be damaged when the foliage is close to or touching fruit, or when fruit is in clusters. The fruittree leafroller has only one generation a year and is rare in commercial orchards in Washington, although it is a serious problem in some British Columbia orchards. The European leafroller is found in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. It also has only one generation each year.

Hosts

Pandemis leafroller

The pandemis leafroller was reported as a fruit pest in Washington as early as 1921. In the late 1940s and early 1950s growers reported pandemis leafroller feeding on cherry, apricot and apple in Yakima and cherry in the Wenatchee area. Since the mid-1970s, pandemis leafroller has become a common pest in cherry and apple orchards in Eastern Washington. In 1989, growers reported it as a pest of peach in the Yakima area.

Where pandemis leafroller is a problem in bearing apple, it is often due to infestations in nearby cherry, prune or nonbearing apple orchards. Reduced sprays after cherry harvest allow populations of both pandemis and obliquebanded leafroller to build up and spread to apple orchards. Pandemis leafroller larvae have been found on wild plants such as cottonwood, rose, willow, dogwood, hawthorn, antelope brush, big-leaf maple, chokecherry, lupine and alder. Generally, numbers are low and though wild hosts are potential sources of infestation for commercial orchards they do not pose as great a threat as nearby infested fruit orchards.

Obliquebanded leafroller

The obliquebanded leafroller survives on an even wider range of plants than do the pandemis or fruittree leafrollers. Historically, it has not often been found in apple orchards that are sprayed regularly for codling moth. It has most often been a pest in young apple orchards but is an increasing problem in bearing orchards in Washington. Cherry orchards in The Dalles, Oregon, have reported severe damage from obliquebanded leafroller and it is the dominant leafroller pest in the Milton-Freewater fruit growing area of Oregon.

Fruittree leafroller

The fruittree leafroller is most often a problem on apples, but also attacks apricot, cherry, pear, plum, prune, quince, raspberry, currant, loganberry, blackberry, gooseberry, English walnut, ash, box elder, elm, locust, oak, poplar, willow and rose.

European leafroller

Apple, pear, hawthorn, cherry, currant and privet are the primary hosts of the European leafroller. In Oregon, it is a pest of filberts and is known as the filbert leafroller. It originated in Europe and was introduced to North America in the 19th century. It colonized two separate areas of North America – the Northeast and the Northwest. It is a pest of tree fruits in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon.

Life stages

Egg

Eggs of the pandemis and obliquebanded leafrollers are laid in masses of 50 to 300 on the upper surface of leaves. At first, the egg mass is light green, but as eggs mature they turn light brown. Just before hatching, the dark head of the larva can be seen in each egg. After hatching, egg masses often remain on leaves and are much more visible, appearing white against the dark green leaf.

The egg is the overwintering stage of the fruittree and European leafrollers. Eggs are laid on the bark of the tree trunk or limbs in irregular flat masses. They are covered with a whitish or grayish gelatinous substance. When first laid they are light brown, later turning to dark brown. By spring, egg masses have bleached to a light gray.

Larva

It is difficult to identify the species of young leafroller larvae, especially in the spring. All have green bodies but the head capsule and thoracic shield (the segment just behind the head capsule may range from light brown to black.

When mature, the larvae of the different leafroller species can more easily be distinguished . The pandemis leafroller larva has a light green to light tan head and a light green thoracic shield. The mature obliquebanded larva has a brown to black head capsule and a thoracic shield that varies from brown to dull green. The sides of the thoracic shield are dark brown to black and the leading edge is often white or cream. The mature fruittree leafroller larva has a black head and thoracic shield. The front margin of the thoracic shield may be white or cream colored. It is usually smaller than the obliquebanded leafroller larva. The mature European leafroller has a green body, light to dark brown head and a greenish brown to dark brown thoracic shield. Larvae should be reared to the adult stage to confirm species identity.

A leafroller larva is usually found inside a leaf that has had one side folded and attached to the other, between two leaves attached together, or beneath a leaf attached to an apple with silk webbing. When disturbed, the leafroller larvae will wiggle rapidly backwards, often dropping from its shelter on a slender thread. This behavior distinguishes leafroller larvae from other caterpillars found in the orchard.

Pupa

The leafroller pupa is a typical moth chrysalis. It is light green or greenish brown at first, but soon turns tan and then a darker brown. The pupa develops in a protected place, usually in a folded and webbed leaf. It may be surrounded with light silken webbing, though it does not have a dense silken cocoon. Pupae of all leafrollers look the same. To identify them, keep them in a container until the moth appears.

Adult

The adult pandemis leafroller is a buff or tan colored moth, 1/2 to 3/4 inches (13 mm to 18 mm) long. Its main distinguishing feature is a banding pattern on the wing. When the moth is at rest, a darker tan or brown band obliquely crossing the middle of each wing appears to join at the center. On the leading and trailing edges of the darker band is a narrow, light tan to yellow line separating the darker area from the lighter colored portion of the rest of the wing. Color intensity varies considerably from moth to moth, sometimes making identification difficult.

The obliquebanded leafroller moth is larger and darker than the pandemis leafroller. It is 3/4 to 1 inch (18 mm to 25 mm) long. The banding pattern on the wing is similar, but the leading and trailing edges of the oblique wing bands are darker than the rest of the wing, not lighter as on the pandemis leafroller.

The fruittree leafroller appears fawn or rusty brown with a prominent light triangular spot on the outside edge of the wing. It is 1/2 to 3/4 inch (13 to 20 mm) long. The wings do not have a distinct banded pattern, but have mottled light and dark brown patches interspersed with lighter ones.

The European leafroller about the same size as the fruittree leafroller. It is a chocolate brown color and is darker than the other leafrollers. A distinct dark band runs diagonally across the wing with a dark patch near the base and outer tip in the male. The female has a less distinctive banding pattern.

Life history

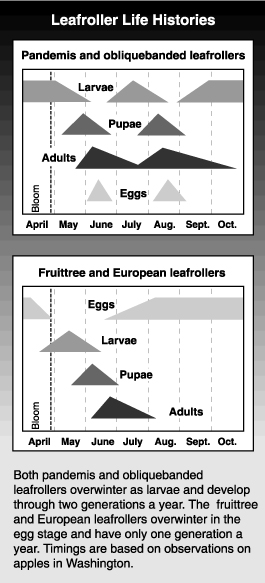

Both pandemis and obliquebanded leafrollers have two generations a year, whereas the fruittree leafroller and European leafroller only have one generation. Pandemis and obliquebanded leafrollers overwinter as second or third instar larvae within a silken case known as a hibernaculum. Hibernacula are found in protected parts of the scaffold limbs, such as pruning scars or small crevices in the bark.

Young larvae of the overwintering generation become active in the spring as fruit buds open. Most larvae have left their hibernacula by the half-inch green stage of apple bud development. They bore into opening buds and later feed on expanding leaves and flower clusters.Larvae are fully grown by mid- to late May. Pupae are present from mid-May through early June. First adults of the overwintering generation appear from late May to early June, depending on spring temperatures. Adult activity peaks about mid-June.

Timing of summer generation egg hatch varies from year to year but is generally from mid- to late June. Larvae mature by late July or early August, and summer generation adult activity peaks in mid- to late August. Eggs of the overwintering generation appear in mid-August. Hatching begins in late August and continues through September and into early October some years. Newly hatched larvae feed for a short time on foliage and fruit before moving to scaffold limbs and building hibernacula in October.

The fruittree and European leafrollers overwinter in the egg stage. Egg hatch begins at about the half-inch green stage of flower bud development and continues until bloom. Larvae feed on leaves, flower parts and young fruit. Larvae mature by mid- to late May. Pupae are present from late May through early June. Adult activity peaks in late June, and the flight may continue into early July.

Females deposit eggs in masses on smooth bark of 1- to 3-year-old wood. The eggs remain there until the following spring.

Damage

Apple

Larvae of all four species feed primarily on foliage. In spring, larvae web together leaves and flower parts of expanding buds, feeding on plant parts within these shelters. As larvae mature, they tend to migrate to growing shoots, where they may web together several newly formed leaves at the shoot tip or make a shelter out of a single leaf. Although larvae do not require fruit to complete their development, they may attach leaves to an apple or use fruit clusters as sheltered feeding sites. Larvae of the obliquebanded and pandemis leafrollers can damage fruit at three periods during the growing season:

- First, larvae of the overwintering generation may eat portions of young fruit in May. If damaged fruit do not abort, they are deeply scarred and severely deformed. This is the only period in which larvae of the fruittree and European leafroller will damage fruit.

- Next, young, summer generation pandemis larvae attach leaves to apples in late June and early July and feed.

- There can be several separate feeding sites within a small area and the feeding is usually no deeper than 1/16 of an inch (1.5 mm).

- As larvae grow, they tend to feed on the foliage of growing shoots. Larger larvae of the obliquebanded leafroller sometimes continue to feed on fruit, causing even more extensive damage. Both types of feeding damage scab over by harvest and are often surrounded by lighter colored areas on the fruit where leaves were attached.

- The third period when fruit may be damaged is just before and during harvest.

- Larvae of the overwintering generation may attach leaves to fruit after hatching from egg masses in late August or early September and feed on the fruit.

- The young larva chews a small hole through the skin of the apple and feeds on the apple flesh. While the pin-hole sized feeding sites usually occur singly, several may be found close together.

The damage is difficult to detect at harvest but becomes obvious as the apple flesh around the feeding sites decays or dries during storage. Feeding damage from this period is often mistaken as codling moth damage.

The distribution of leafroller larvae and feeding damage depend on tree size and type. In large trees, there can be 2 to 10 times more larvae in the upper half than the lower half. Spur varieties tend to have more fruit damage than nonspur varieties. That is because fruit and leaves are closer together in spur varieties, which increases the likelihood of leaves touching fruit and providing feeding shelters for the larvae.

Cherry

Overwintering larvae can damage young cherries in the spring, but most damaged fruit abort, so are not on the tree at harvest. Young, summer generation larvae of the pandemis or obliquebanded leafroller feed on cherries just before harvest and have been mistaken as larvae of the cherry fruit fly by fruit inspectors

Other tree fruits

Damage to other fruit crops is usually caused by surface feeding. Damage to pear, prune and apricot can be severe if leafroller populations are not managed.

Monitoring

Pheromone traps can be used to monitor male leafroller activity. The pheromone of the threelined leafroller, Pandemis limitata, is used to monitor the pandemis leafroller. If leafroller populations are moderate to high, traps may be filled with moths in one night. This makes it difficult to pinpoint peak activity unless the traps are checked daily. A new trap bottom should be installed after 50 or more moths are captured.

Moth capture in pheromone traps has not been a good indicator of leafroller population density or potential damage. Capture of 15 or fewer moths per week usually, though not always, indicates little potential for damage, but higher numbers do not always mean there will be damage. Male leafrollers of some species can travel long distances, and high numbers may be captured in orchards where chances of larval infestations are low. Female pandemis leafrollers do not move very far, often only a few yards from where they emerge, before laying their first egg mass. Sampling leafroller larvae in the spring is difficult. Larvae of pandemis and obliquebanded leafrollers begin attacking fruit buds as soon as they open (at green tip). Most pandemis leafroller larvae have left their hibernacula and are feeding in buds by the half-inch green stage of apple bud development. Emergence of obliquebanded leafroller larvae from hibernacula may extend over a longer period.

Between green tip and tight cluster leafroller larvae are difficult to detect by visual examination in the field. To accurately estimate leafroller density at this time, collect buds in the field and return to the laboratory or office and examine under magnification. Collect at least 150 fruit buds (6 buds from 25 trees) from a block (5 acres). Due to the time required to collect and examine this sample it has limited value as a management tool but can be used to determine if a delayed-dormant control is necessary.

By the tight cluster or pink stage of apple bud development larvae can be detected without magnification, as webbing and feeding damage is more obvious. Examination of at least 20 fruit buds from 20 trees will provide a good estimate of larval density during this period. As shoots begin to elongate, leafroller larvae move and start to feed at growing points. In trees over 10 feet (3 meters) tall, more pandemis leafroller larvae are in the upper half of the canopy. Sample from that part of the tree to avoid underestimating the density.

In summer, young pandemis larvae are difficult to detect. They remain in the fruiting canopy where they spin small, webbed shelters near the mid-vein on the undersides of leaves or attach leaves to fruit and feed on both. When pandemis larvae are about half grown, they feed on leaves at the tip of growing shoots. Larvae of the obliquebanded leafroller tend to move to shoot tips sooner than pandemis. The easiest way to determine leafroller presence is to examine 20 shoots per tree on 20 trees per block in late July or early August. While this sample is relatively easy to make, it occurs after most fruit damage has been done. However, it is a good indication of larval density and if fruit should be protected prior to harvest.

Biological control

Leafrollers have many natural enemies. Several species of parasitic wasps and a parasitic fly attack leafroller larvae. Most of these parasitoids have larvae that develop inside the leafroller larvae, existing only to pupate. However, the larva of one species, Colpoclypeus florus, feeds externally. Parasitoid larvae or pupae, or their empty pupal cases, can often be found with dead leafroller larvae still inside the rolled leaf. The potential for biological control of leafrollers is low in orchards using insecticides to control codling moth and other insects. However, in orchards using mating disruption and soft chemicals for pest control, the impact of parasitoids on leafroller populations can increase dramatically. For more information on the biology and identification of common parasitoids of leafrollers, refer to Predators and Parasitoids.

Management

The fruittree and European leafrollers are usually controlled by insecticides applied during the prebloom period for other insects, and these species have not been reported as serious problems in Pacific Northwest orchards. Following are management guidelines for the pandemis leafroller, most of which also apply to the obliquebanded leafroller.

The best strategy to manage leafrollers is to control larvae of the overwintering generation in spring. Conventional insecticide applications in the delayed-dormant period (at half-inch green tip stage of apple flower bud development) have given the best control of pandemis leafroller. Bacterial insecticides-strains of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt)-have given good control of leafroller larvae when 2 or 3 applications have been made in the period from tight cluster through petal fall.

In summer, insecticides can be used to control either adults or larvae. Sprays targeting adults should be timed at peak moth flight. In most years, the second cover spray directed at codling moth coincides fairly well with the peak flight of pandemis leafroller adults and is a reasonably good timing for adult control. Peak pandemis moth flight can be predicted using degree-days. The first moths emerge about 950 degree-days after January 1. First moth capture in pheromone traps is used as a biofix, similar to the codling moth model, to predict future events in the life history of pandemis leafroller. At biofix, the degree-day value is set at zero. Moth flight peaks between 200 and 220 degree-days after first catch.

Summer sprays should target young larvae before they can damage fruit. Pandemis leafroller egg hatch begins about 420 degree-days after first moth catch. Chemical controls should be applied between 420 and 450 degree-days so that residues remain during the hatch period. If insecticides with short residual activity are used, such as Bt products, a second or even third treatment may be required at intervals of 7 days. Egg hatch is complete by 1,000 degree-days.

Controlling pandemis or obliquebanded leafrollers as larvae or adults in late summer (late July though August) is very difficult and normally should not be considered. If, however, more than 5% of the shoots are infested in late July, some type of control may be needed to protect fruit from injury before and during harvest. Bt sprays have been effective against larvae feeding in shoot tips during late July and early August.

Timing of sprays to control adults in the second flight is difficult. The second flight begins about 1,600 degree-days after first moth catch in the spring and peak flight is between 2,300 and 2,350 degree-days, usually in mid-August. The second egg hatch period begins at 2,750 degree-days, usually in late August or early September.

Pandemis leafroller has different developmental thresholds than the codling moth. The lower threshold is 41°F and the upper 85°F. A degree-day look-up table is available.

Leafroller Gallery

Materials available for apple

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Materials available for pear

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Materials available for sweet cherry

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Use pesticides with care. Apply them only to plants, animals, or sites listed on the labels. When mixing and applying pesticides, follow all label precautions to protect yourself and others around you. It is a violation of the law to disregard label directions. If pesticides are spilled on skin or clothing, remove clothing and wash skin thoroughly. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

YOU ARE REQUIRED BY LAW TO FOLLOW THE LABEL. It is a legal document. Always read the label before using any pesticide. You, the grower, are responsible for safe pesticide use. Trade (brand) names are provided for your reference only. No discrimination is intended, and other pesticides with the same active ingredient may be suitable. No endorsement is implied.

Contact

Tianna DuPont, WSU Tree Fruit Extension Specialist

Tianna DuPont, WSU Tree Fruit Extension Specialist

Tree Fruit Research & Extension Center, Wenatchee, WA

tianna.dupont@wsu.edu, (509) 663-8181

Articles from the Tree Fruit website may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Reprint articles with permission must include: Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension Fruit Matters at treefruit.wsu.edu and a link to the original article.