by Elizabeth H. Beers, Michael W. Klaus, and Eric LaGasa, originally published 1993

Enarmonia formosana (Scopoli) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

Cherry bark tortrix has been a pest in Europe and Siberia for many years and is widespread throughout the British Isles. It was first discovered in North America in 1990 in southern British Columbia and in Washington State in 1991.

Hosts

The common name is somewhat misleading as this insect attacks most tree fruits, not just cherry. Its hosts also include plum, peach, nectarine, apricot, almond, apple, crab apple, pear and ornamental cherry. In England, it is primarily a pest of older trees that are more likely to have winter injury or wounds. Stone fruit trees, which tend to have more bark injury, may be more vulnerable than other fruit trees.

Life stages

Egg

The egg is round, flat and slightly dome shaped and measures about 1/40 inch (0.7 mm) in diameter. It is white when laid, but turns pink with a deeper colored center it develops. Eggs are usually laid singly, although sometimes in groups of two or three, slightly overlapped.

Larva

The larva is about 3/8 inch (8 to 11 mm) long and has a yellowish brown head and pale gray body. The anal plate is the same color as the rest of the body, but with a grayish brown spot.

Pupa

The pupa is yellowish brown with bands of spines on the dorsal side of the abdomen.

Adult

The adult has ochre-yellow forewings, which are intricately patterned with dark brown and metallic grey and have white lines on the outer margin. The hind wing and abdomen are dark grayish brown.

Life history

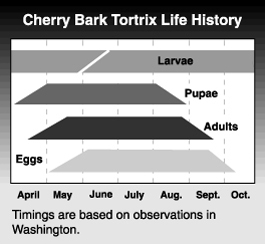

In Washington, the adult moth is active from April to September and has one generation a year. It flies mainly in the early morning but also during the day.

In Washington, the adult moth is active from April to September and has one generation a year. It flies mainly in the early morning but also during the day.

Mated females lay eggs on the bark of the tree, often near wounded or previously infested areas. Pruning scars and winter damaged areas are likely targets. Each female lays about 90 eggs, which hatch within 2 to 3 weeks. The larvae, which pass through five instars, feed beneath the bark, making irregular tunnels. Cherry bark tortrix overwinters as a larva, which pupates the following spring. After the adult has emerged, the cast pupal skin protrudes from the tunnels in the bark.

Damage

The feeding tunnels of larvae loosen and crack the bark. Gummosis, often mixed with silk and frass (small pellets of insect excrement) oozes from the cracks. The bark sustains most of the damage, although there can be some damage to the cambium layer. Heavy infestations cause swellings and cankers and can eventually kill limbs or entire trees. On apple, damage is usually confined to the undersides of the main scaffolds. On cherry, the base of the trunk is more often attacked. Larvae often attack pruning scars on branches or any area on the trunk or limbs that has been damaged, such as limb rubs caused by support wires.

Monitoring

A simple, but time consuming method of monitoring is to examine injured bark for signs of gummosis and frass. Frass can easily be seen at tunnel openings in late winter and early spring. However, several native clear-wing moths in the Sesiidae family cause similar damage to the trunk and scaffold limbs. To identify the pest, the larvae must be collected and examined.

Cherry bark tortrix is attracted to a blend of tortricid pheromone components. Use of pheromones can simplify monitoring in regions not know to be infested, but they are not useful in managing established infestations due to the long flight period of adults.

Management

Control aimed at adults is not practical because of the prolonged flight period. Most of the available information on control of the pest is outdated. In England, spring treatments aimed at killing larvae as they came to the surface of the bark to pupate were not successful. Another approach in England in the 1960s was a dormant season treatment aimed at the overwintering larvae using materials such as tar oil, creosote or insecticides. However, the treatments were extremely labor intensive, as the materials were brushed onto the tree after the bark had been scraped, and the insecticides used are no longer available. Materials currently used for sesiid borers, such as the peachtree borer, may be effective.