by Everett C. Burts and John Dunley, originally published 1993

Pseudococcus maritimus (Ehrhorn) (Homoptera: Pseudococcidae)

The grape mealybug was originally described as a pest of grapes, but it can attack most deciduous fruit crops. Since the 1970s, it has become an increasingly severe pest of pear and apple. It is slow to spread from orchard to orchard, but once an orchard is infested, the infestation is difficult to clean up. It is usually only a problem on large, mature trees, which are difficult to spray thoroughly and provide shelter for the mealybugs.

Hosts

Grape mealybug attacks many plant species including all tree fruits grown in the Northwest as well as other rosaceous plants, grapes, ornamental trees and shrubs. This insect is able to develop new host strains, which allows it to adapt to more hosts. Adaptations may include different development rates and numbers of generations per year.

Life stages

Egg

The egg is a salmon colored, elongated oval. Eggs are laid in masses of waxy filaments that have a cottony appearance.

Nymph

The first instar nymph, or crawler, is pink to salmon colored and has well developed legs. The crawler is covered with a light coating of waxy granules, giving it the appearance of being coated with flour. After settling to feed, the crawler molts into a sedentary nymph, and the coating of wax becomes heavier. The sedentary nymph has poorly developed legs. It is pink to purple, but the waxy filaments give it a whitish cast.

Adult

The adult female is wingless and looks similar to a nymph. It can be up to 3/16 inch (5 mm) long. It has a well developed ring of waxy filaments around the sides of its body. Filaments are longest at the posterior end of the body and become progressively shorter towards the front of the body. The adult male is much smaller than the female and has wings held flat over the back. It is a fragile insect and resembles a male scale.

Life history

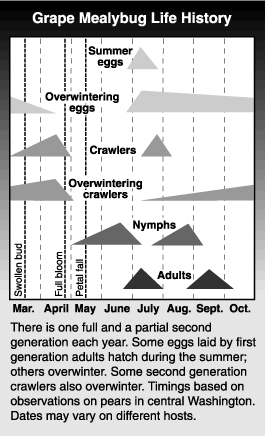

Grape mealybugs overwinter as eggs or crawlers within the loose cottony egg sac under bark scales on scaffold limbs, in other sheltered places on trees, or in duff at the bases of trees.

Grape mealybugs overwinter as eggs or crawlers within the loose cottony egg sac under bark scales on scaffold limbs, in other sheltered places on trees, or in duff at the bases of trees.

Crawlers start emerging from egg sacs at the beginning of bud swell and begin feeding on the bases of buds. When buds open they go directly to new shoots and leaves. Because some overwintering sites are exposed to sun while others are shaded, crawler movement occurs over a long time, ending at about petal fall. First generation nymphs mature during late June and July in the Northwest. Adult males appear first, mate with last instar nymphs or adult females and die. Receptive females release a pheromone to attract males. Mated females migrate to sheltered areas, lay eggs and die in the egg sac. A partial second generation matures in late August and September. Nymphs of this generation sometimes settle in or around the fruit calyx.

Damage

The most obvious damage by grape mealybug results from the honeydew it secretes. Honeydew is cast off in small drops and falls down through the canopy. When it lands on fruit it causes a coarse, black russet, which is similar to pear psylla russeting. However, mealybug russeting is scattered over the fruit surface, while honeydew from psylla is in patches or streaks. Mealybug russeting is most common in low centers of trees, whereas psylla damage occurs more evenly over the trees or in the tops.

When mealybug populations are dense, they may enter the calyx ends of fruit, causing contamination problems on processed fruit. Their feeding softens tissue in the calyx and around the seed cavity. Symptoms resemble those of a disorder called pink end.

Monitoring

There are no established treatment or damage thresholds for grape mealybug. When infestations are detected they usually need to be controlled. Check during the dormant season for eggs and crawlers in egg sacs under bark scales on scaffold limbs and in other protected areas on trees. The white cottony mass makes egg sacs easy to see. During delayed-dormant and clusterbud stages, crawlers can be monitored by examining developing buds on short limbs and spurs arising from scaffold limbs in low centers of trees. It is easy to detect infestations in late June or July when mature females are crawling back to larger limbs to deposit eggs or during harvest when damaged fruit is evident in bins. However, little can be done to control mealybugs at these times. If the infestation is spotty, as it often is when this pest first invades orchards, mark infested trees so they can be given special attention.

Biological control

The predator-parasitoid complex that attacks grape mealybug in orchards has not been thoroughly studied. Many generalist predators, such as lacewings, ladybird beetles and predaceous bugs, will feed on this pest. An encyrtid egg parasitoid, Acerophagus notativentris, is common in infested orchards. Grape mealybug populations are generally reduced to nondamaging levels by natural control in orchards where soft pesticide programs are used for a few years.

Management

Chemical control

Chemical control of grape mealybug works best when sprays are aimed at the crawler stage. Once crawlers settle and cover themselves with wax they are less susceptible to chemicals, as are crawlers still in the egg sac. Crawlers emerge from egg sacs over a long period. First generation emergence continues from delayed-dormant stage of tree development to petal fall. Effective chemical residues must be maintained throughout that period. A series of sprays, including delayed-dormant, clusterbud and petal fall applications, is required to control first generation crawlers. The two most effective times to spray are clusterbud and petal fall. Both sprays are needed and good spray coverage is essential. If possible, apply succeeding sprays at right angles to the preceding one to improve coverage of hard-to-hit areas of trees. Scaly areas on trunks and limbs and sucker crowns in the tops of trees should be sprayed with a handgun.

Grapy Mealybug Gallery

Materials available for apple

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Materials available for pear

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Materials available for stone fruit (not cherry)

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Cultural practices

Certain cultural practices can reduce the severity of grape mealybug attack. This pest is more difficult to control on large, old trees with high scaffold limbs and large sucker crowns. Pruning out sucker crowns, removing high scaffold limbs during winter pruning and removing water sprouts (suckers) from scaffold limbs through the center of trees during early summer not only removes tender growth susceptible to attack by mealybugs but also improves spray penetration. Pull water sprouts by hand, rather than cut them with loppers, to minimize regrowth. This should be done before sprouts develop woody attachment to limbs, normally before the end of June.

Use pesticides with care. Apply them only to plants, animals, or sites listed on the labels. When mixing and applying pesticides, follow all label precautions to protect yourself and others around you. It is a violation of the law to disregard label directions. If pesticides are spilled on skin or clothing, remove clothing and wash skin thoroughly. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

YOU ARE REQUIRED BY LAW TO FOLLOW THE LABEL. It is a legal document. Always read the label before using any pesticide. You, the grower, are responsible for safe pesticide use. Trade (brand) names are provided for your reference only. No discrimination is intended, and other pesticides with the same active ingredient may be suitable. No endorsement is implied.