by Jay F. Brunner and Richard E. Rice, originally published 1993

Grapholita molesta (Busck) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

The oriental fruit moth originated in China. It was introduced in the United States from Japan on flowering cherry about 1913 and is now found in all fruit growing regions of the United States, southern Canada and northern Mexico. It is also common throughout Europe, Asia, Australia and South America. The larvae bore in shoots or feed in fruit.

Hosts

Although the primary hosts of the oriental fruit moth are peach and nectarine, it will also attack quince, apricot, apple, plum, cherry, pear, rose and flowering cherry. While common in some eastern apple-growing districts, infestations of apple are rare in the Northwest.

Life stages

Egg

Egg

The egg is a small, flat, oval disc, which is white at first but changes to amber.

Larva

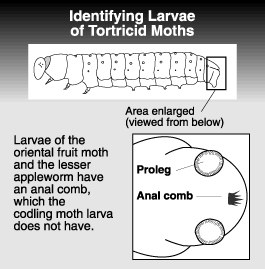

The larva has 4 or 5 instars. The newly hatched larva is white or cream with a black head. When full grown, it measures 3/8 to 1/2 inch (8 to 13 mm). It has a brown head capsule and thoracic shield and a pinkish or creamy white body. It can be distinguished from a codling moth larva by the presence of an anal comb, which is lacking in the codling moth larva.

Pupa

The pupa is contained within a cocoon found in a sheltered place, such as under a bark scale or litter at the base of a tree. It changes from yellowish brown to reddish brown as adult emergence nears.

Adult

The adult oriental fruit moth is gray and measures about 1/4 inch (5 mm). The wings have indistinct light and dark bands, giving the moth a salt-and-pepper appearance.

Life history

The oriental fruit moth overwinters as a fully grown larva in a hibernacula of silk webbing, either in tree crevices or in the ground cover. It pupates in the spring. Moths of the overwintering generation first appear when peach is in bloom. Eggs are laid on the foliage, usually on the upper sides of leaves of terminal growth. A female can produce up to 200 eggs. Incubation can take anywhere from 5 to 21 days depending on the temperature.

The oriental fruit moth overwinters as a fully grown larva in a hibernacula of silk webbing, either in tree crevices or in the ground cover. It pupates in the spring. Moths of the overwintering generation first appear when peach is in bloom. Eggs are laid on the foliage, usually on the upper sides of leaves of terminal growth. A female can produce up to 200 eggs. Incubation can take anywhere from 5 to 21 days depending on the temperature.

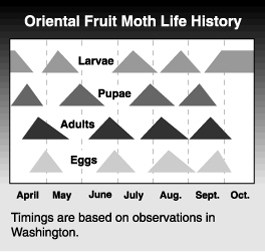

First generation larvae feed by boring into the growing shoots. They reach maturity by mid- to late May. First generation moth flight is from early June through mid-July. There are 3 to 4 flights per year in Washington. Some second and most third and fourth generation larvae attack fruit before seeking overwintering sites where they spin cocoons.

Damage

First and second generation larvae tend to damage mainly shoots, while most of the injured fruit is due to third and fourth generation larvae. The oriental fruit moth attacks succulent terminals of rapidly growing twigs during spring and early summer.

A newly hatched larva enters the tender, growing shoot at its tip, near the base of a young leaf. An immature larva that has abandoned an old, injured twig enters a new one at the axil of a fully developed leaf. The larva bores inside the twig, working its way down the shoot for 2 to 6 inches (5 to 15 cm). When the larva matures or no longer finds the twig desirable, it makes an exit hole and leaves. If it needs more food to develop fully, it may enter another twig or a fruit.

Infested twigs usually have wilted leaves. If an upright twig has one small, wilted leaf, it means the larva has entered within the last day or two. As the larva moves down into the twig, more leaves wilt. The number depends how far the larva penetrates. If a twig is dark colored or has dry leaves and gummy ooze, the larva has left.

When twigs of young trees are attacked, lateral shoots form below the damage. Young trees under severe and continued attack become bushy. In nurseries, shoots of recently budded peach are sometimes attacked, resulting in crooked stems.

Fruit of peach and nectarine can be damaged early in the season by partly grown larvae after they leave shoots. They usually feed on the side of the fruit, causing gumming with brown sawdust-like frass. As fruit grow, they become deformed, and the more severely damaged fruit may drop. Fruit are more often attacked when nearing maturity. Newly hatched larvae usually, though not always, enter through the stem end. They bore through the flesh to the pit of peaches and nectarines, where most of the feeding is done. When mature, larvae move to the fruit surface, making a round exit hole. Larvae feed only on one fruit and do not move from fruit to twigs.

Apples infested with oriental fruit moth larvae look similar to those infested by codling moth. However, the codling moth larva tunnels directly to the core and feeds on the seeds, whereas the burrows of oriental fruit moth are smaller and follow a more meandering course, not necessarily to the core. Oriental fruit moth larvae do not push frass to the surface of infested fruits as do codling moth larvae.

Monitoring

Damage to shoot tips looks like that caused by the peach twig borer. Examine growing shoot tips while the first generation larvae are active. Infested shoots will be wilted. Pheromone traps can be used to monitor adult moths. Traps should be placed in the orchard prior to peach bloom and monitored daily until the first moth is observed. Good trap maintenance and care are important for good information.

Biological control

The braconid wasp Macrocentrus ancylivorus, which is native to North America, is a leafroller parasite that has adapted to the oriental fruit moth. Females lay eggs in young oriental fruit moth larvae. The larva of the parasitoid larva develops and matures when the host cocoons.

Management

Chemical control of the oriental fruit moth can be improved by using a degree-day model to establish optimum timing, as with codling moth. The target of control sprays is the young larvae before they have bored into shoots or fruit. Development thresholds for oriental fruit moth are 45°F and 90°F, whereas those of the codling moth are 50°F and 88°F. Also, the method of calculating degree-days is slightly different in that a vertical cutoff is used instead of a horizontal one. Refer to the degree-day look-up table to calculate degree-days.

Moth capture in a pheromone trap is used to establish biofix, the start of degree-day accumulation. When the first moth is captured, the degree-day total is set at zero. According to research in California, the best time to apply control sprays is between 500 and 600 degree-days after biofix. Good control of the first generation larvae in late April or early May may mean no further controls are necessary for the rest of the year. The generation of oriental fruit moth lasts about 1000 degree-days. Thus, if sprays are required for the second generation they should be applied at 1500 to 1600 degree-days after biofix. These degree-day timings have not been thoroughly tested in Washington but have worked very well in California.

Mating disruption

Mating disruption has proven to be a successful control for oriental fruit moth. Dispensers should be placed in the orchard before the April moth flight. In warm years, or in orchards with high moth populations or outside pressure, a second application of dispensers may be needed. Dispenser types that last only 2 months may also require multiple applications.

Oriental Fruit Moth Gallery

Materials available for stone fruit (not cherry)

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Use pesticides with care. Apply them only to plants, animals, or sites listed on the labels. When mixing and applying pesticides, follow all label precautions to protect yourself and others around you. It is a violation of the law to disregard label directions. If pesticides are spilled on skin or clothing, remove clothing and wash skin thoroughly. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

YOU ARE REQUIRED BY LAW TO FOLLOW THE LABEL. It is a legal document. Always read the label before using any pesticide. You, the grower, are responsible for safe pesticide use. Trade (brand) names are provided for your reference only. No discrimination is intended, and other pesticides with the same active ingredient may be suitable. No endorsement is implied.

Articles from the Tree Fruit website may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Reprint articles with permission must include: Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension at treefruit.wsu.edu and a link to the original article.