by Stanley C. Hoyt, originally published 1993

Quadraspidiotus perniciosus (Comstock) (Homoptera: Diaspididae)

San Jose scale is a key pest in almost all the fruit growing districts of the United States. It was introduced to California from China on flowering peach in the early 1870s and soon became a serious pest in the San Jose area. By the late 1890s it had spread to all parts of the United States.

The scale is a tiny insect that sucks the plant juices from twigs, branches, fruit and foliage. Although an individual scale cannot inflict much damage, a single female and her offspring can produce several thousand scales in one season. If uncontrolled, they can kill the tree as well as make the fruit unmarketable.

San Jose scale is a problem particularly in large, older trees where it is difficult to achieve good spray coverage, but young, unsprayed trees may also be vulnerable. The pest has become of increasing concern to the Northwest tree fruit industry due to the importance of exports, as phytosanitary regulations bar infested fruit from some countries.

Although scale lives primarily on the tree bark, surviving under scales and in crevices, the first indication it is in the orchard may be small red spots on the fruit or leaves.

Hosts

San Jose scale is most destructive on apple and pear, but it can be a serious pest of sweet cherry, peach, prune and other tree fruits. It also attacks nut trees, berry bushes and many kinds of shade trees and ornamental shrubs. Infestations in backyard or wild trees can spread to nearby orchards.

Life stages

Crawler

The female San Jose scale produces live young. The newly hatched crawler of either sex is yellow. It has six legs, two antennae and a bristle-like sucking beak that is almost three times the length of its tiny, oval body. The crawler seeks a suitable site to settle and immediately begins to secrete a waxy covering over its body, which hardens into a scale. The scale turns from white to black and then to gray and goes through several molts before maturing. The differences in sexes become apparent after the first molt, although the scales covering them are identical. The females are smaller and rounder than the males and have lost their eyes, legs and antennae. The males have eyes but no legs or antennae.

Adult

The mature male is a very small, yellowish-tan insect with wings and long antennae. The female is wingless and legless, and its yellow body is soft and globular. The covering of a full grown female is about the size of a pin head, with a central, nipple-like bulge. The color is often obscured by a sooty fungus.

Life history

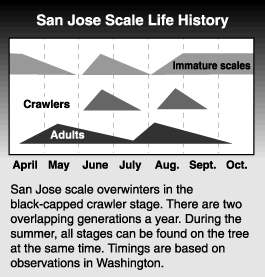

San Jose scale has two generations a year in Washington. It overwinters in the black-capped, immature stage. Being unable to move, the scales must survive wherever they happen to be on the tree, and in severe winters many may be killed. Scales that are further developed than the black-cap stage in the fall are usually killed by cold weather. Increased scale problems can be expected after mild winters. In the spring, surviving scales continue to mature.

San Jose scale has two generations a year in Washington. It overwinters in the black-capped, immature stage. Being unable to move, the scales must survive wherever they happen to be on the tree, and in severe winters many may be killed. Scales that are further developed than the black-cap stage in the fall are usually killed by cold weather. Increased scale problems can be expected after mild winters. In the spring, surviving scales continue to mature.

After developing through larval and pupal stages, the males mature and back out from their scales about 4 to 6 weeks after birth. Adult males fly for only a few days and are capable of mating immediately with the females, which remain under their scales. Female scales release a pheromone to attract males for mating. Each female produces several hundred live crawlers over a 6-week period. Timing of the different stages varies from year to year, depending on temperatures. Usually, crawlers of the first generation appear in early June and may continue to be produced until early August.

The young crawlers move over the plant during the first few hours of their lives. They can be carried to other trees by the wind, on the feet of birds, on the clothing of farm workers or on orchard equipment. Within a few hours they settle on the bark, leaves or fruit, insert their long, bristle-like beaks, and begin feeding and forming a scale covering. Females of the first generation mature in late July, and second generation crawlers appear in August. The two generations often overlap, and during the summer all stages can be found on the tree at the same time. Second generation crawlers continue to be produced until October or November.

Damage

If neglected, scale populations can quickly grow into a problem because the insect multiplies so rapidly. An infested apple can have 1,000 or more scale on it. A red spot will appear around the scales as they start to feed on the fruit, and often the feeding causes a slight depression. The spots are a brilliant red at first, but as the fruit grows and the spots increase in size, they fade to light red or pink. On red apples, spots are difficult to see. Trees infested with San Jose scale produce small, immature apples, and infested apples do not color properly. If the trees are seriously infested, the apples crack and have a musty smell. The pest can be detected in an orchard bin or in the packing house by the odor.

Besides making fruit unmarketable, San Jose scale kills twigs and limbs. If not controlled, it can kill the tree. More commonly, infestations of San Jose scale are light in commercial orchards. A small number of scales will infest an occasional fruit in or near the calyx. These scales may be difficult to locate on the sorting table. Packed fruit may be rejected, particularly in export markets, if it has scale or markings from scale feeding.

Monitoring

It is usually not practical to sample to determine density or potential for fruit infestation, because the pest is seldom distributed uniformly throughout a tree and may infest only a few trees in an orchard block. However, if scale-infested fruit are found after the first generation of crawlers have settled, measures against the second generation are indicated.

Scale may be noticed during pruning or on fruit as it is harvested. In cherry orchards, leaves of scale infested trees do not drop in fall, making it easy to detect infested areas of the orchard. Mark infested areas as they are noticed so they can be given special attention when control treatments are applied. Place two-sided sticky tape on small limbs in infested areas to determine when crawlers are active, or use the degree day model to time summer sprays.

Adult male flight can be monitored with pheromone traps. However, it has been difficult to relate trap catch with potential fruit damage. A biofix can be established using the traps, and development can be predicted using a degree day model (see section on Management below).

Biological control

Several parasites and predators attack San Jose scale. In Washington, the parasitoids recorded from San Jose scale include Encarsia perniciosi and Aphytis sp. Although they destroy many scales, they do not provide enough control to prevent damage. Natural enemies may become numerous in orchards that are not sprayed with insecticides, but even under these conditions biological control has not been adequate. Currently, biological controls are only a supplement to chemical control. Management

San Jose scale was the first known insect in the United States to show resistance to a pesticide. Its resistance to lime-sulfur was reported in Washington in 1908. It caused tremendous damage and killed many trees before better chemical controls were found. Scale can develop rapidly in young, unsprayed trees, and scattered trees in the orchard may become encrusted with scale. New plantings should be checked annually. Where young trees are interplanted in old infested orchards, they quickly become infested. In older orchards, infestations may be spread to the top of the trees by birds and may go unnoticed for several years until scales are visible on the fruit.

The best approach to orchard protection is to prevent scales from becoming established. This can be done by treating the orchard annually before bloom when buds are beginning to open and good spray coverage of the tree can be achieved. If infestations become heavy, particularly on older, large trees, the insects may get under bark scales or on top of high leaders where they are difficult to target. Additional sprays, possibly by hand gun, may be needed for a few years to reduce populations. Summer sprays directed at the crawler stage help protect fruit but usually do not control infestations. For this reason, they are a supplement to the early season spray, not a substitute.

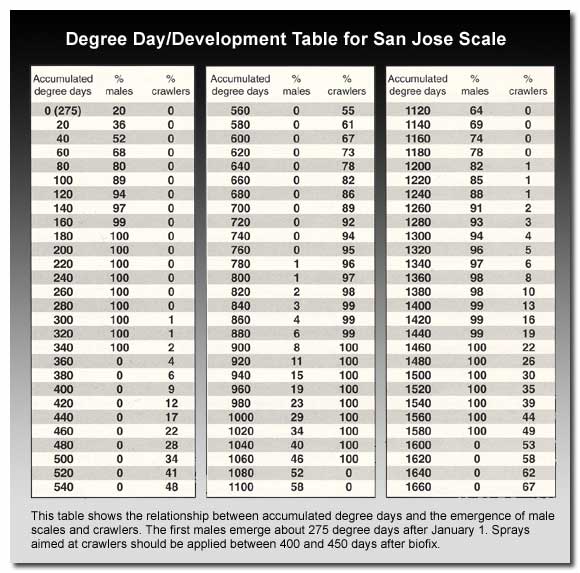

A degree day model is helpful for timing crawler sprays in June. The lower and upper developmental thresholds of San Jose scale are 51°F and 90°F. A degree day look-up table based on these thresholds is below. The model should be started at first male scale capture in a pheromone trap (the biofix). Because male scale flight is difficult to monitor accurately in commercial orchards, the regionally established biofix for codling moth is often used to start the San Jose scale model, as the flight of both insects commonly begins on the same day. If neither biofix is available, start the model at full bloom of Red Delicious. Apply sprays aimed at crawlers between 400 and 450 degree days after biofix. This timing is usually close to the second cover spray for codling moth. The degree day table shows the relationship between degree days and the emergence of male scale and crawlers. It is important to examine young trees not receiving a full spray program. Control of infestations in the early stages will not only protect tree vigor but will prevent them from spreading to other trees in the orchard.

References consulted

Unruh, T. 2010. Personal communication regarding parasitoid species found on scale in the early 1990s.