by Louis Nottingham and Betsy Beers, September 26, 2017

Pear Psylla, Cacopsylla pyricola (Förster) (Figure 1), is probably the most challenging insect pest to Washington pear growers. Nymphs feed on leaves and excrete a liquid known as “honeydew”, consisting mostly of water and sugar (Figures 1 & 2). Honeydew is a nuisance to field workers, may lead to leaf necrosis and will eventually drip onto fruit leading to marking and discoloration known as “russet” (Figure 3).

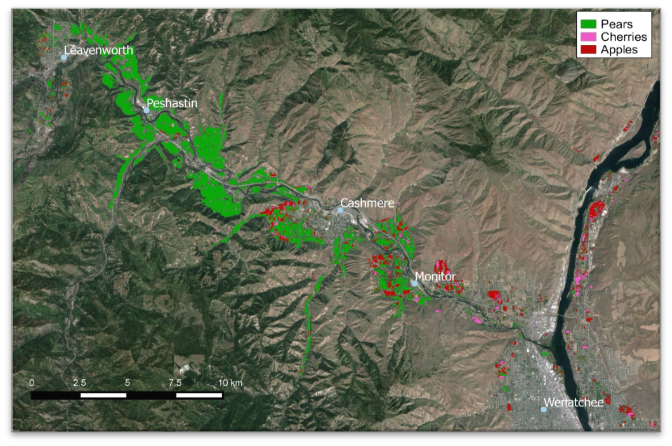

Pear psylla is difficult to manage for many reasons, with a key challenge stemming from the sheer length of this pest’s seasonal activity. Adults begin mating and laying eggs in late February to early March, and nymphs and adults will continue to thrive well past pear harvest in late summer. Adults are very mobile and can disperse across distances of at least a few miles, maybe more (D.R. Horton, personal communication); therefore, disparities in spray timing and control level from orchard to orchard allows psylla to continuously redistribute, thwarting the ability to gain long-term control from an individual treatment. In the Wenatchee Valley, small-acreage pears blocks dominate the agricultural landscape (Figure 4), exacerbating the challenge from adult dispersal. In the past, large-scale approaches (such as area-wide coordinated spraying) greatly reduced the valley’s psylla population to a more manageable level (Burts 1968). Unfortunately, those programs are no longer in place.

In addition to the long season and inter-orchard mobility, pear psylla’s unique overwintering biology adds another layer to the management challenge. Psylla overwinter as adults called “winterforms”, which exhibit a partial migration out of orchards once pear leaves fall in October. In other words, some remain in the orchard in which they developed, while others move to alternate hosts. Vagrant winterforms can survive on a wide range of hosts including (but not limited to): apple, forsythia, Oregon grape, flowering quince, yucca, and various conifers (Horton 2016). The proportion of psylla that leave the orchard may vary from year to year, and orchard to orchard. Some evidence has shown that when fall weather is cold and wet, more psylla remain in the orchard; while warm and dry conditions promote migration to alternate hosts (Horton 2016). Blocks that have dense psylla populations are also likely to have higher rates of outward dispersal to alternate hosts or other orchards (Fye 1983). Psylla then redistribute evenly in the spring, suggesting that psylla are not inclined to return to the same orchard from which they came (Fye 1983).

Why is this important?

Psylla overwinter very successfully in the Wenatchee Valley, which leads to massive numbers of egg-laying adults in the spring; so, targeting the overwintering stage may be a crucial strategy for subduing the overall population. Late winter and early spring sprays targeting winterforms are a common practice for most growers; but unfortunately, they are unlikely to result in regional population suppression for two reasons. First, many growers cannot spray at this time of year due to their inability to drive over steep and soggy terrain, leaving refuge areas for psylla to proliferate. Second, the dispersal period of psylla (either moving back into orchards from alternate hosts, or from densely populated to more sparsely populated orchards) lasts for an extended period from February through April. Even the best early season management will not lead to long-term control, because the regional population remains large and very mobile.

The limitations of early season management have led many to wonder if the post-harvest period may be a more logical time to target overwintering adults with insecticide sprays, for the goal of suppressing the regional population. The advantage of targeting the winterforms in the late summer or early fall is that they are relatively sedentary up until leaf-fall (Horton 2016), providing a window-of-opportunity for targeting psylla with foliar sprays. Post-harvest sprays would not act as a replacement for spring sprays; but they could increase the success of all management techniques for the following year due to reduced overall population.

Of course, there are challenges that need to be addressed before the implementation of post-harvest sprays. Most importantly, because this method is meant to suppress the regional population, it will require area-wide execution. Because many winterforms will travel off-site during the winter, intermix, and then redistribute in the spring, a post-harvest knock-down is unlikely to have much effect on a small scale (unless, perhaps, a block is very isolated). This means that various members of the industry (growers, consultants, and researchers) will have to work together to coordinate a joint effort. Not only is area-wide coordination imperative, but this effort also requires effective product(s) and adequate coverage. Both remain uncertain for this time of year, due to the lack of materials that effectively kill older nymphs and adults, combined with the inherent difficulty of penetrating full foliage on older trees. Finally, specific timing of a regional post-harvest spray must be determined. Should post-harvest sprays occur all at once after the entire valley has finished harvesting, or instead, block-by-block following the harvest of each orchard? Overcoming these challenges is not out of reach, but will require further study and planning among researchers and industry members. The prospect of a post-harvest area-wide spray program will likely be key topic of discussion during the upcoming winter months.

Contact

Louis Nottingham

Postdoctoral Research Associate, WSU Entomology, TFREC

louis.nottingham@wsu.edu

This project is supported in part with funding from the Tree Fruit Research Commission.

References

Burts, E. C. 1968. An Area Control Program for the Pear Psylla. J. Econ. Entomol. 61: 261-263.

Fye, R. E. 1983. Dispersal and Winter Survival of the Pear Psylla. J. Econ. Entomol. 76: 311-315.

Horton, D. R. 2016. Key Psylla Biology: Winterform Stage. Pear Day Presentation, Wenatchee WA.