WSU Tree Fruit IPM Strategies

Written by Shashika Hewavitharana, WSU; Tianna DuPont, WSU Extension; Mark Mazzola, USDA-ARS

Peer reviewed publication (downloadable PDF): WSU Publications FS323E

Replant disease is a widespread problem in intensive tree fruit and nut growing areas. It is characterized by reduced productivity in fields repeatedly planted to the same or closely related tree fruit or nut crops. It can also occur in tree fruit and nut nurseries. In a fruit-bearing orchard the disease can cost growers more than $70,000 to $150,000 an acre due to reduced productivity during the first four years of orchard planting (Mazzola 2005, Mazzola 2010, Mazzola 2015). It is also called by multiple names such as soil sickness, soil exhaustion, replant disorder, and replant problem. While abiotic factors such as soil fertility, degraded soil structure, residual herbicide activity, and phytotoxicity from hydrolysis of cyanogenic compounds found in plant roots have been linked to replant disease, the majority of research evidence suggest that it is due to biotic factors or increased activity of harmful soil microorganisms. In this factsheet we will describe symptoms, disease causing organisms and management recommendations.

Symptoms

The disease symptoms are visible shortly after planting new trees. Uneven growth over the orchard block, stunting, and shortened internodes can signify replant disease in the orchard. When a tree is uprooted, discolored roots, root tip necrosis, and reduced root biomass can be seen. Young trees may die within the first year. Many will survive but overall fruit production and quality are reduced.

Causal Organism and Disease Cycle

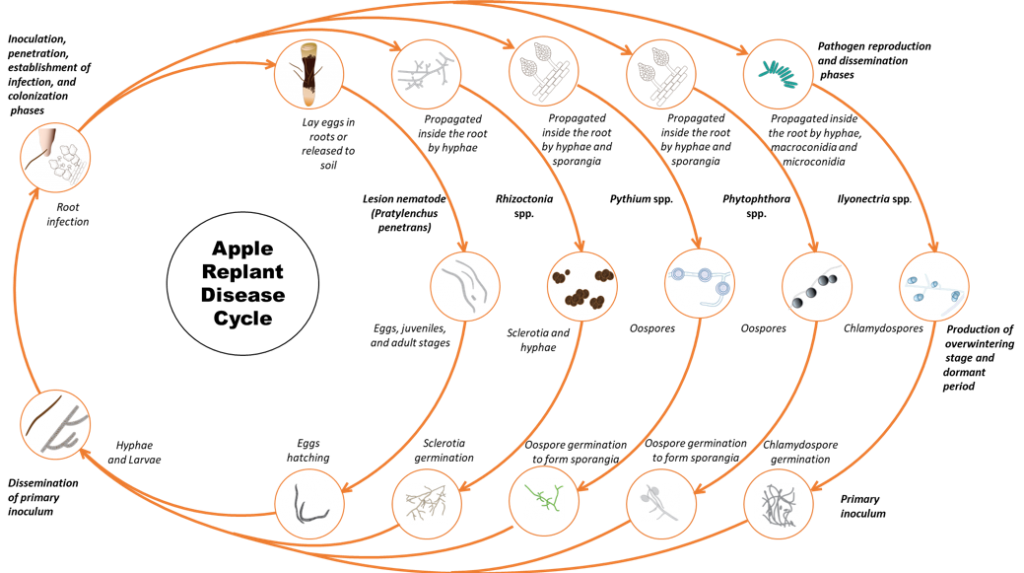

The disease is caused by a pathogen complex that consists of fungi, oomycetes (fungi-like organisms) and nematodes. Individual sites may have one or multiple organisms causing the syndrome (Figure 1). In Washington State, the disease is caused by multiple species within several genera of fungi: Rhizoctonia, Ilyonectria; oomycetes: Phytophthora, Pythium and in some sites lesion nematode Pratylenchus penetrans (Mazzola 1997, 1998).

Contaminated soil, irrigation water, or planting stock can all be sources of inocula. The fungal and oomycete pathogens produce overwintering structures like sclerotia (Rhizoctonia), chlamydospores (Ilyonectria), and oospores (Phytophthora and Pythium) that can survive in dead or dormant roots and soil. Lesion nematodes survive in the soil and plant residues as eggs and as multiple generations of juveniles and adults. (Agrios 2005). Once the new trees are planted or during the spring when dormant roots become active, the pathogen propagules germinate and parasite nematode eggs hatch in response to exudates from the roots. The fungi and oomycete mycelia grow from the propagules and infect the fine roots. While fungi such as Rhizoctonia cause extensive root rot, Pythium spp. cause a more insidious level of damage by stripping root hairs resulting in diminished capacity of the plant to take up water and nutrients. Lesion nematode can directly penetrate roots at a variety of stages (II stage juvenile, II stage juvenile, III stage juvenile, IV stage juvenile, and adults). Lesion nematode feeds from outside and inside the root. Feeding of the nematode kills root cells and when the nematodes move through the root they damage and disrupt root tissue inhibiting water and nutrient movement into the plant. Feeding damage also provides access channels for fungi, bacteria and other organisms. Oomycete pathogens in the complex can be dispersed by free water during irrigation as they have motile spores called zoospores.

Cultural Controls

Plant nematode-free trees

If the nursery site where trees were propagated had significant replant disease pressure young trees likely carry inocula in the roots which may serve to infest a grower’s site.

Crop rotation

Many other crops can host the pathogens in this complex, thus crop rotation is not a guaranteed strategy to lower potential disease pressure. However, a five year plus rotation to a non-woody crop can help reduce pressure. For small-scale, soil in the planting hole can be replaced with good quality soil from a non-orchard site. In order to effectively replace the soil, the planting hole should be 7 feet (length) X 7 feet (width) X 2 ½ feet (depth) (Benson 1976); (Smith 1994).

Water management

- Limit periods of soil saturation. Oomycetes in the apple replant disease complex can disperse between trees if the soil is saturated, conditions that will also aid the root infection process. Dispersal of the pathogen can be reduced by minimizing periods of soil saturation.

- Choose well drained soils. Choose orchard sites with good drainage.

- Maintain and improve soil structure. Add organic matter to improve aggregate stability and water infiltration and reduce compaction.

Choose tolerant rootstock

The most important cultural control you can use is a disease tolerant rootstock. Apple rootstock varieties have varying levels of tolerance to replant disease (Table 1). In general, Geneva series rootstocks are tolerant to the disease while, Malling or Malling-Merton series rootstocks are susceptible to the disease (Leinfelder 2006). Some rootstocks are moderately tolerant to the disease. Tolerant rootstocks for cherry and pear have not yet been reported.

Table 1: Tolerance levels of different rootstocks to replant disease

(Atucha 2014, Fazio 2004, Isutsa 2000, Leinfelder 2006, Yao 2006)

| Tolerant | Moderately tolerant | Susceptible |

|---|---|---|

| G935 | G11 | G13 (CG.4013) |

| G30 | G16 | M7 |

| G65 | M9 | |

| G210 | M26 | |

| G41 | MM106 | |

| G214 | MM111 | |

| M9.Nic 29 |

Planting position

Planting in old inter-row grass lanes has improved the tree growth. Planting in old grass strips spatially avoids the areas where soil contamination by pathogens is highest (Leinfelder 2006).

Chemical Controls

Soil fumigation

Two registered soil fumigants have shown long-term efficacy in Washington orchard trials: metam sodium (or metam potassium), and 1,3 dichloropropene/ chloropicrin. It is important to follow soil temperature and preparation guidelines prior to fumigation. Usually optimum soil conditions are in October and early November, and in April or later in spring. Cool, wetter, and finer texture soil will retain the fumigants longer and therefore have higher efficacy. To prevent phytotoxicity to new trees delay tree planting after fumigation for the period recommended on the label. Dig planting holes, disturb the planting area, or work the soil a few days before planting.

- 1,3 -Dichloropropene plus chloropicrin. e.g. InLine, Tri-Form 80, Telone C-17 (Leinfelder 2006), Telone C-35. Untarped shank and tarped shank injection have different rates of application. Follow the label specification. 1,3-dicloropropene is nematicidal while the chloropicrin is fungicidal.

- Metam Sodium or Metam Potassium. Metam is a water-soluble liquid which is moved through irrigation water into the targeted soil zone. After the downward movement is stopped the fumigant converts into methyl-isothiocyanate, a more toxic gas which only moves a few inches. Therefore, it is important that the liquid solution moves to the desired depth. The most effective rate identified is 75 gallons per treated surface acre.

- Potassium N-methyldithiocarbamate. e.g K-PAM® HL- liquid soil fumigant that can be applied using chemigation, soil injection or soil bedding.

- Metam Sodium (Sodium methyldithiocarbamate).g. Metam CLRTM 42%, Sectagon-42®, Vapam® HL. Some products are soil fumigant solutions that is compatible with chemigation, soil injection or soil bedding equipment.

- Metam Potassium (Potassium methyldithiocarbamate)g. Metam KLRTM 54%, Sectagon-K54®. Soil fumigant solution that is compatible with chemigation, soil injection or soil bedding equipment.

- Dazomet, eg Basamid, is also a Methyl isothiocyanate (MITC) The product is a granular.

Biofumigants and Biopesticides

Biopesticides are certain types of pesticides derived from natural materials such as animals, plants, bacteria, and certain minerals. Several new biofumigants/biopesticides are labeled. Only limited data is available about efficacy of these products.

- Allyl isothiocyanate. g Dominus® Broadcast application, flat fume application, chemigation

- Azadirachtin- botanical nematicide g. Ecozin® Plus 1.2 % ME (emulsifiable concentrate)

Use pesticides with care. Apply them only to plants, animals, or sites listed on the labels. When mixing and applying pesticides, follow all label precautions to protect yourself and others around you. It is a violation of the law to disregard label directions. If pesticides are spilled on skin or clothing, remove clothing and wash skin thoroughly. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

YOU ARE REQUIRED BY LAW TO FOLLOW THE LABEL. It is a legal document. Always read the label before using any pesticide. You, the grower, are responsible for safe pesticide use. Trade (brand) names are provided for your reference only. No discrimination is intended, and other pesticides with the same active ingredient may be suitable. No endorsement is implied.

References

Agrios, G. 2005. Plant Pathology. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Atucha, A., Emmet, B., Bauerle, T. L. 2014. “Growth rate of fine root systems influences rootsotck tolerance to replant disease.” Plant Soil no. 376:337-346.

Benson, N.R. 1976. “Retardation of apple tree growth by soil arsenic residues.” J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. no. 101 (3):251-253

Fazio, G. and Mazzola, M. 2004. “Target traits for the development of marker assisted selection of apple rootstocks-prospects and benefits.” Acta Horticulturae no. 663:823-828.

Isutsa, D.K., Merwin, I. A. 2000. “Malus Germplasm varies in resistance or tolerance to apple replant disease in a mixture of a New York orchard soils.” Hortscience no. 35 (2):262-268.

Leinfelder, M. M. and Merwin, I. A. 2006. “Rootstock selection, preplant soil treatments, and tree planting positions as factors in managing apple replant disease.” Hortscience no. 41:394-401.

Mazzola, M. 1997. “Identification and pathogenicity of Rhizoctonia spp. isolated from apple roots and orchard soils.” Phytopathology no. 87:582-587.

Mazzola, M. 1998. “Elucidation of the microbial complex having causal role in the development of apple replant disease in Washington.” Phytopathology no. 88:930-938.

Mazzola, M. and Brown, J. 2010. “Efficacy of Brassicaceous seed meal formulations for the control of apple replant disease in conventional and organic production systems.” Plant Disease no. 94:835-842.

Mazzola, M., and Mullinix, K. 2005. “Comparative field efficacy of management strategies containing Brassica napus seed meal or green manure for the control of apple replant disease.” Plant Disease no. 89:1207-1213.

Mazzola, M., Hewavitharana, S. S., and Strauss, S. L. 2015. “Brassica seed meal soil amendments transform the rhizosphere microbiome and improve apple production through resistance to pathogen reinfestation.” Phytopathology no. 105:460-469.

Smith, T. J. 1994. “Successful management of orchard replant disease in Washington.” Acta Horticulturae no. 363:161-167.

Yao, Shengrui, Merwin, I.A., Brown, M.G. 2006. “Root dynamics of apple rootstocks in a replanted orchard.” Hortscience no. 41 (5):1149-1155.

Contact

Tianna DuPont, WSU Tree Fruit Extension Specialist

Tianna DuPont, WSU Tree Fruit Extension Specialist

Tree Fruit Research & Extension Center, Wenatchee, WA

tianna.dupont@wsu.edu, (509) 663-8181

Articles from the Tree Fruit website may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Reprint articles with permission must include: Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension Fruit Matters at treefruit.wsu.edu and a link to the original article.

[/textblock][/column][/row]