Written by Dowen Jocson, PhD student WSU Entomology. February 15, 2020

Insects communicate in many forms like with chemicals in the form of pheromones, or with vibrations in the form of songs like in cicadas and grasshoppers. Pear psylla, Cacopsylla pyricola, uses both pheromones and songs to find and attract their mates. Unlike cicadas and crickets, pear psylla is an important pest in pear orchards. Learning and understanding how they find their mates can help us develop a disruption tool to decrease reproduction rates of this psylla. Less mating, less psylla. Makes sense right?

In 2018, I started working with Dr. Dave Crowder, Dr. Elizabeth Beers, and Dr. David Horton to develop a mating disruption tool. Our first step in developing a mating disruption tool for psylla is to listen and understand mating behaviors, specifically pear psylla courtship songs. Our human ears cannot hear these courtship songs; instead, they are heard through the stem by the mechanical sensors in the psylla’s legs. Unlike cicadas and crickets that make airborne vibrations that we can hear, psylla and a majority of the insect world use substrate-borne vibrations to communicate. This just means that they use their body to vibrate the stems. These vibrations form a pattern that are species-specific, which means that only pear psylla will recognize that they are from another pear psylla. Because of this specificity, they can be used in targeted pest management.

Pear psylla vibrations can be detected by special equipment like an accelerometer or laser vibrometer. This equipment translates these vibrations to a sound wave we can record and listen to on the computer. This is our way of eavesdropping on their “romantic” conversations. We can then record and observe their behavior to learn more about what we can use for managing them.

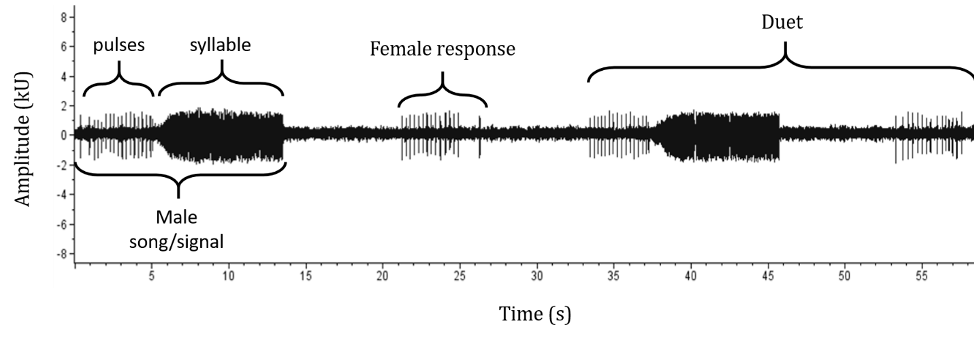

So far, what we know is that males produce songs that consist of a set of pulses and a syllable (Figure 1). These are advertisement songs to let the females know what their options are. If the females like a particular male song, she will respond to it with her own set of pulses (Figure 1). This is called a duet. To hear the duet click here. The duet facilitates male mate-searching behavior for females on the same plant. Think of this as a game of Marco Polo. The male sings. The female responds. Then the male walks toward where he thinks the female response is coming from. This continues until the male finds the females. The idea of the mating disruption is to lessen the likelihood of the males and females meeting up to mate.

It seems straightforward, but many environmental factors can affect this mating behavior. For one, temperature can influence how male songs are produced and possibly perceived. Our data suggests that the syllable in the male songs can change pitch or frequency (Hz) as temperature changes. As temperature increases, the syllable gets higher in pitch. Another part of the song that temperature affects is the pulses, in the beginning of their song. We have recorded faster pulses in higher temperatures compared to lower temperatures. So what does this all have to do with developing a mating disruption tool? To be more effective, we have to account for temperature fluctuations experienced by the psylla in the orchard. This also means that winterforms and summerforms could sound different. Our recordings suggest that winterforms have a lower pitch than summerforms. In terms of singing, winterforms sing bass while summerforms sing tenor.

At this moment, we have just scratched the surface. We know that psylla use vibrations to communicate with each other and to find mates. We know aspects of their mating behavior like duetting and mate searching. However, we still have work to do before we can apply this to orchards. Despite that, we think that there is great potential in this type of IPM because it encourages targeted management, less chemicals, and is more of a cultural practice.

Contact

Dowen Jocson

Dowen Jocson

Department of Entomology

Washinton State University

Pullman, WA 99163

dowen.jocson@wsu.edu

treefruit.wsu.edu articles may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Reprint articles with permission must include: Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension at treefruit.wsu.edu and a link to the original article.