Written by Lynn Sosnoskie, WSU Weed Science. April 10, 2017

Weed size is a significant factor influencing the management of weeds with foliar applied herbicides. Larger weeds are notoriously difficult to control, as compared to smaller-sized plants. Herbicide escapes can compete with the current crop by competing for light, nutrients, and water. Weed escapes can also affect crop performance in following seasons via the seeds that they contribute to the soil seedbank.

Weed management is essential during the establishment phase of orchards to improve the survival of newly transplanted nursery stock. In commercially bearing systems, weeds must be controlled in order to increase irrigation efficiency, provide equipment access, and ensure that fruits can be harvested effectively and economically. Furthermore, non-managed weeds may support populations of insect, vertebrate, and pathogenic pests that can significantly reduce tree health over time.

Weed control strategies may not always be 100% effective and escapes can occur for numerous reasons. Situations leading to herbicide failure include: improper herbicide selection or inappropriate timing of chemical applications, unfavorable weather conditions at the time of treatment, reduced herbicide activity due to poor water quality, and the development of herbicide resistance in the target weed population, among others. Plant size can also affect weed control; the efficacy of post-emergence herbicides is often diminished when products are applied to large/mature plants (Figure 1).

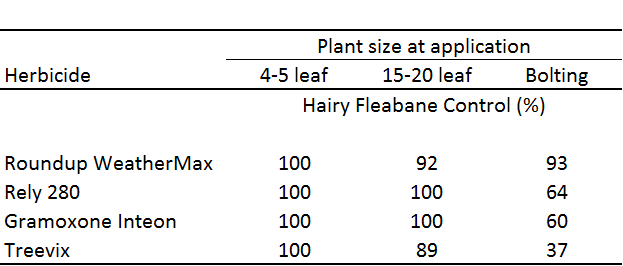

As an example: weed scientists at the University of California, Davis, recently undertook studies to describe how the control of hairy fleabane (Conyza bonariensis), a close relative of marestail/horseweed (Conyza canadensis), differed with respect to plant size at the time of herbicide application. Treatments included: glyphosate (Roundup WeatherMax® at 3.5pt/A), glufosinate (Rely® 280 at 3 pt/A), paraquat (Gramoxone Inteon® at 3pt/A), and saflufenacil (Treevix® at 1 oz/A) applied at one of three different growth stages: small rosette (4- to 5-leaf, < 1 inch height), large rosette (15- to 20-leaf, < 7 inches in height), and bolting (> 20 leaves, 7 inches in height).

Greater than 90% control of hairy fleabane was achieved when plants were treated with glyphosate, regardless of size at the time of application (Table 1). Glyphosate is a systemic herbicide that it is translocated within treated plants; it eventually accumulates at meristems and inhibits the production of aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine) that are needed for protein synthesis. Conversely, the efficacy of glufosinate, paraquat, and saflufenacil decreased when hairy fleabane plants began to bolt (Table 1). Unlike glyphosate, these active ingredients exhibit no or limited mobility in treated plants; as a consequence, herbicide-induced injury is limited to the tissues that come into contact with the spray solution. In the case of larger plants, the outermost portions of the canopy can act as a shield for the innermost leaves, stems, and buds, which may continue growing. Additionally, contact herbicides will not impact underground tissues (roots, rhizomes, bulbs, etc.), which also support plant regrowth. This isn’t to say that weed size isn’t a concern when applying systemic products, it certainly is, only that the effects of incomplete coverage are often more dramatic with contact products.

Still, it isn’t sufficient to focus on in-season weed control as the sole metric of efficacy. Plants that escape treatment may reach reproductive maturity and produce viable seeds. These seeds are the foundation for weed problems in future years. As a consequence, weed escapes necessitate that growers engage in additional management practices that may have been unplanned and that add to the cost of crop production. Increased seedbank/in-field weed densities could also facilitate the development of herbicide resistance. When weed infestations are heavy, the probability of selecting for resistance can be high, even if the mutation rate that leads to the development of resistance is low.

There are several steps that growers can take to maximize weed control with post-emergence herbicides, including timing applications to treat weeds while they are small and tender. Additional strategies include: selecting the appropriate herbicides to control target weed species and applying them at appropriate rates, minimizing off-target movement due to rain and wind, calibrating spray equipment, properly, and using adjuvants, effectively, to ensure coverage and penetration. To minimize the potential for herbicide resistance, growers should diversify their chemical, cultural, and physical weed control strategies as much as is environmentally and economically possible.

Disclaimer: No endorsement is intended for products mentioned, nor is lack of endorsement meant for products not mentioned. The author and Washington State University assume no liability resulting from the use of pesticide applications detailed in this report. Application of a pesticide to a crop or site that is not on the label is a violation of pesticide law and may subject the applicator to civil penalties up to $7,500. In addition, such an application may also result in illegal residues that could subject the crop to seizure or embargo action by WSDA and/or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It is your responsibility to check the label before using the product to ensure lawful use and obtain all necessary permits in advance.

Contact

Lynn M. Sosnoskie, Ph.D.

Assistant Research Faculty, Washington State University

Tree Fruit Research and Education Center

Wenatchee, WA 98801

@LynnSosnoskie on Twitter

Phone: 229-326-2676