by Jay F. Brunner, originally published 1993

(Hymenoptera: Eulophidae)

This small eulophid wasp is the most common parasite of the western tentiform leafminer in the Pacific Northwest. Its life history is well synchronized with that of the leafminer. P. flavipes can kill more than 90% of the leafminers in a generation. Its activities against the leafminer are usually so effective that chemical controls are not needed. It is an ectoparasite, which means it feeds externally on its host rather than within the host’s body.

P. flavipes is a chalcidoid wasp (Superfamily Chalcidoidea). Chalcidoids are 1/10 to 1/8 inch (2 to 3 mm) long and are often a dark metallic blue or green. They have clear wings with few veins, and in some families (such as Mymaridae) the wings are merely stalks with hairs. These small wasps attack the eggs, larvae or pupae of many different insects, including important fruit pests. It is estimated that there are over 25,000 described species, and probably many more that are undescribed. There are more than 2,000 species of chalcid wasps in North America. Many species have been imported into the United States to control pests. The Chalcidoids include the Eulophid, Encyrtid, Trichogrammatid, and Mymarid parasitic wasps.

Life stages

Egg

The egg is white and cylindrical and is laid inside the leafminer mine.

Larva

The larva is maggot-like, with a legless, elongated body that is 1/100 to 1/10 inch (0.3 to 2.5 mm) long. It is generally white, though the brown contents of the gut may be visible through the skin, especially in larger larvae.

Pupa

The pupa is black and is from 1/20 to 1/10 inch (1.3 to 2.5 mm) long. Unlike the pupa of the western tentiform leafminer, its head, thorax and abdomen are visible. It can also be distinguished by its shorter, more robust shape and darker color.

Adult

The female P. flavipes usually has a dark-colored thorax with blue metallic reflections and a yellow and black abdomen. The male has similar coloring but is smaller than the female and has branched antennae.

Life history

There are at least three complete generations of the parasitoid each year. It overwinters primarily as a pupa within mines of leaves on the orchard floor. In some years it may also overwinter as a larva. Unlike its host, P. flavipes seems to anticipate the change of seasons and in the fall stops development at the pupal stage. Thus, proportionally more parasites may survive the winter in an orchard than leafminers, giving the parasite a distinct advantage in the spring, which is usually when parasitism levels are highest.

Adult parasitoids emerge in the spring at about the same time as the leafminer. Female parasitoids search leaves for mines and attack the larvae. Female parasitoids lay eggs primarily in the mines of tissue-feeding larvae. Parasitoids are in the orchard 2 to 3 weeks before most tissue feeders and survive during this period by feeding on sap feeders, an activity known as ”host feeding.” After the first generation, P. flavipes generations tend to overlap, so all stages of the parasite are in the orchard at any time. Leafminer generations also tend to overlap later in the season, providing a constant source of tissue feeders for the parasites to attack.

When a female parasitoid finds a sap feeding mine, it will most often sting the larva, paralyzing it. As its stinger is withdrawn from the sap feeding mine, a material is secreted that forms a tube connecting the larva to the surface of the mine. The parasitoid then feeds on the contents of the sap-feeder larva through this tube. Host feeding can account for 10 to 25% of the deaths caused by P. flavipes. The female parasitoid may deposit an egg in the mine after stinging the larva but only if the last sap feeder stage (third larval instar) is present. Adult parasitoids produced from eggs laid in sap feeder mines are always males.

When a female parasitoid finds a tissue-feeding mine, it will sting the larva, paralyzing it. Usually an egg is deposited within the mine but not necessarily on the leafminer larva. When the egg hatches, the parasitoid larva crawls to the paralyzed leafminer and feeds. Parasitoids emerging from tissue-feeding mines are about half males and half females. Between 40 and 75% of leafminers are killed this way. Occasionally, the female parasitoid will sting a tissue-feeding larva, paralyzing it without depositing an egg. The leafminer larva eventually dies but no parasitoid is produced. This type of attack usually accounts for less than 10% of leafminer mortality. Larvae of the parasite pupate inside the mines. Emerging adults escape from the mine by chewing a small, circular hole through the leaf. This evidence can help determine the level of parasitism in an orchard.

Management

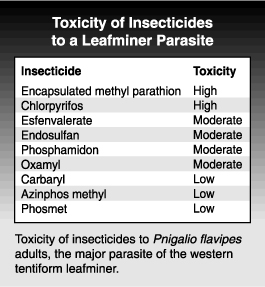

Assess parasitoid levels at the end of the first and second leafminer generations to determine the potential for biological control. Parasitism levels of 35% or greater in each leafminer generation are usually sufficient to keep leafminer populations below treatment thresholds. If parasitism is below 20%, it is likely the leafminer will exceed treatment thresholds at some time during the year. Biological control can be improved by avoiding chemical controls for other pests when adult parasites are active, which is roughly the same time as leafminer adults are active. Certain insecticides applied at the wrong time of year, when adult parasitoids are active, tend to disrupt biological control of the leafminer.

Assess parasitoid levels at the end of the first and second leafminer generations to determine the potential for biological control. Parasitism levels of 35% or greater in each leafminer generation are usually sufficient to keep leafminer populations below treatment thresholds. If parasitism is below 20%, it is likely the leafminer will exceed treatment thresholds at some time during the year. Biological control can be improved by avoiding chemical controls for other pests when adult parasites are active, which is roughly the same time as leafminer adults are active. Certain insecticides applied at the wrong time of year, when adult parasitoids are active, tend to disrupt biological control of the leafminer.