After a tough year in 2017 lets look at the answers to common questions about cherry powdery mildew answered by WSU plant pathologist Dr. Gary Grove.

by Gary Grove, WSU Plant Pathology; Tianna DuPont, WSU Extension. December 11, 2017

Why was Cherry Powdery Mildew so bad in 2017?

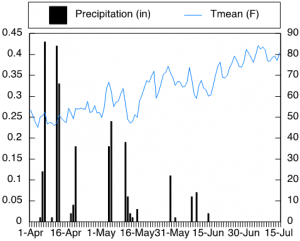

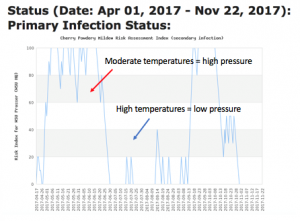

May and June in Washington were relatively cool and precipitation was sufficient to meet the wetting requirements for primary infection. Temperatures of 70°F to 80°F favor the disease. “The disease had it way too good for way too long.” This meant high disease pressure. Additionally, in many places the late winter made it difficult to get early sulfur sprays applied because of the amount of snow still on the ground. “When you have a mild spring you have to be careful.” “Part of the problem this year was the mild spring.”

|

|

| Figure 1. Temperatures in 2017 were conducive to the pathogen. | |

Where did we see blocks with high powdery mildew pressure?

Mildew was a problem many places this year due to the mild spring and the availability of carryover inoculum from 2016. But environmental factors contributed to problem blocks. Blocks of large trees with too much shade and not enough air flow maintained favorable conditions for the disease. Blocks in shaded canyons that did not dry out were sometimes more susceptible. We also do not know the extent of FRAC Group 7 (strobilurin) fungicide resistance in the PNW cherry industry.

How does the fungus overwinter and where does powdery mildew start in the tree?

Powdery mildew overwinters in hard shelled spore containers called chasmothecia. Chasmothecia were produced on leaves that were affected the previous growing season. Chasmothecia are readily dispersed by wind and splashing water and can overwinter in bark fissures and plant debris in tree crotches. The chasmothecia contain 8 spores called ascospores (figure 3). Ascospores are released in response to precipitation or irrigation water. Ascospores land on cherry foliage, germinate, and establish infections. In the spring primary mildew colonies are first observed on the undersides of leaves produced directly on scaffold limbs or those near tree crotches (figure 4). These primary mildew colonies produced millions of secondary spores (conidia) that spread and intensify the epidemic.

When I am spraying, what are the most important areas to cover?

Cherry powdery mildew can only infect young leaves. We don’t know exactly why this is. Perhaps because of the thicker cuticle on older leaves or because the spores are hydrophobic and stick better to younger leaves. Since cherry powdery mildew can only infect young leaves, those are the most important leaves to cover. It is therefore imperative to ensure fungicide coverage of new foliage via good spray coverage and appropriate spray timing.

What is the most important thing I can do to control Cherry Powdery Mildew next year?

Begin your fungicide spray program early! Pruning your trees this winter is the most important thing. If canopies are dense the humidity stays high which favors mildew (figure 5). Trees without an open canopy are also difficult to spray well and get good coverage.

Which sprays should I use when?

While the pressure is lower at the beginning of the season chose your less effective materials. These will generally give you brown rot control and some powdery control. It is generally a good idea to reserve your more effective materials for June nearer to harvest. Group 7 and 11 pesticides (Luna Sensation, Pristine, and Merivon) have shown good control on fruit as well as leaves and fit well in this end of the spray season sprays. Make sure to rotate between FRAC groups in order to reduce the risk of building pathogen resistance. In a cooler spring you can add in sulfur applications (below 85 F temperature). Sulfur can be very effective when applied at short intervals and can break up your rotation of sprays leaving the heavy hitters for the end.

Will the heat in July and August slow it down?

Yes. Temperatures of 70 F to 80 F are most favorable for cherry powdery mildew. At 86 F (30 C) it slows down. For example, at 68 F (20 C) it takes 14 days to form a colony and at 86 F (30 C) it can take 3 weeks.

If we have another cool spring next year is there anything we can do knowing that pressure will be higher?

Yes. In a mild spring it is important to begin your fungicide spray program early and keep a tighter interval between your sprays. Additionally, you can use sulfur at temperatures below 85 F as part of your spray schedule. Sulfur kills the fungus not only through direct contact but also through gases it releases.

Have you found much resistance to the fungicides we are using?

We are doing another screen now with colonies collected in the Cashmere and Malaga areas. However, in recent screenings, high risk fungicides including Fontelis and Quintec which have been used heavily have demonstrated reduced efficacy in some areas. Some resistance to Group 3 compounds (DMI) was documented in Oregon back in the 2000’s.

I have a lot of powdery mildew up high in the trees. What should I do?

Trees that are too tall are often impossible to get good spray coverage and so they then have powdery mildew up in those high branches (figure 6). It is unlikely that those high parts of the tree are helping you from a fruit quality standpoint either. Prune your trees to make them shorter this winter. If you prune out those tall parts of the tree this winter and there was a lot of mildew up in that area, you likely have a lot of the overwintering chasmothecia on those branches.

What should I do about root suckers?

Root and scaffold suckers are a perfect refuge for powdery mildew. They continue to supply young susceptible tissue later into the season and are rapidly colonized by the fungus (figure 7). They often stay moist from the irrigation and they are often missed by the sprayers. Keep up your management of root suckers, generally with a burn down herbicide. Remove scaffold suckers by hand.

What is the best way to scout for mildew in my cherries?

You will find mildew on the young tissue. The first mildew colonies are normally encountered on the underside of immature leaves near tree crotches or near the bark of scaffold limbs. Later, look for the initial secondary mildew colonies on the youngest leaves on first-year wood. If you don’t find it there move on to another tree.

Summary

- A severe powdery mildew year (such as 2017) ensures carryover inoculum for the next year.

- Be aware that mild springs may have higher powdery mildew pressure.

- Prune this winter to open up your canopies and bring the height down!

- In a mild spring consider including sulfur or oils in your sprays when temperatures are appropriate.

- Properly calibrate your sprayer to optimize coverage.

- Always spray under good conditions with effective materials at appropriate intervals.

- Use materials with some potential resistance early when pressure is lower.

- Use high efficacy materials close to harvest.

- Rotate between fungicide classes (FRAC codes) to reduce resistance risk.

- Manage your root and scaffold limb suckers. Their foliage is extremely susceptible to powdery mildew and the fungus produces billions of spores (conidia) on them. Conidia blow to other leaves and fruit and initatiate new infections, thus increasing the severity of the disease epidemic.

Contacts

Professor

WSU Prosser IAREC

Phone 509-786-9283

grove@wsu.edu

WSU Extension

(509) 663-8181

tianna.dupont@wsu.edu