Written by David Horton, USDA-ARS, Wapato, December 22, 2025

Overview

Cacopsylla pyricola – commonly referred to as pear psylla or just psylla – is the key insect pest in pear orchards of the Pacific Northwest. Pear psylla is native to Europe, likely entering North America through the northeastern U.S. as a hitchhiker on pear stock from Europe. Entry occurred in the early-1800s, or a full century before the pest’s arrival in the Pacific Northwest. What may not be fully appreciated by a North American audience is that our psyllid is but one member of a large complex of pear psyllids that spans the region between Western Europe and Eastern Asia. Size, color, geography, and lifecycle vary among species. Cacopsylla pyricola is the sole member of this group to have made it to North America. A surge in the importing of pear trees from Western Europe in the early-1800s led to psylla’s entry into the eastern US. This article examines these events. One conclusion to emerge is that C. pyricola – with one other species – is the only pear psyllid to have had the right mix of biological traits and European geography to make that early-1800s transatlantic jump into eastern North America.

Diversity of the Pear Psyllids

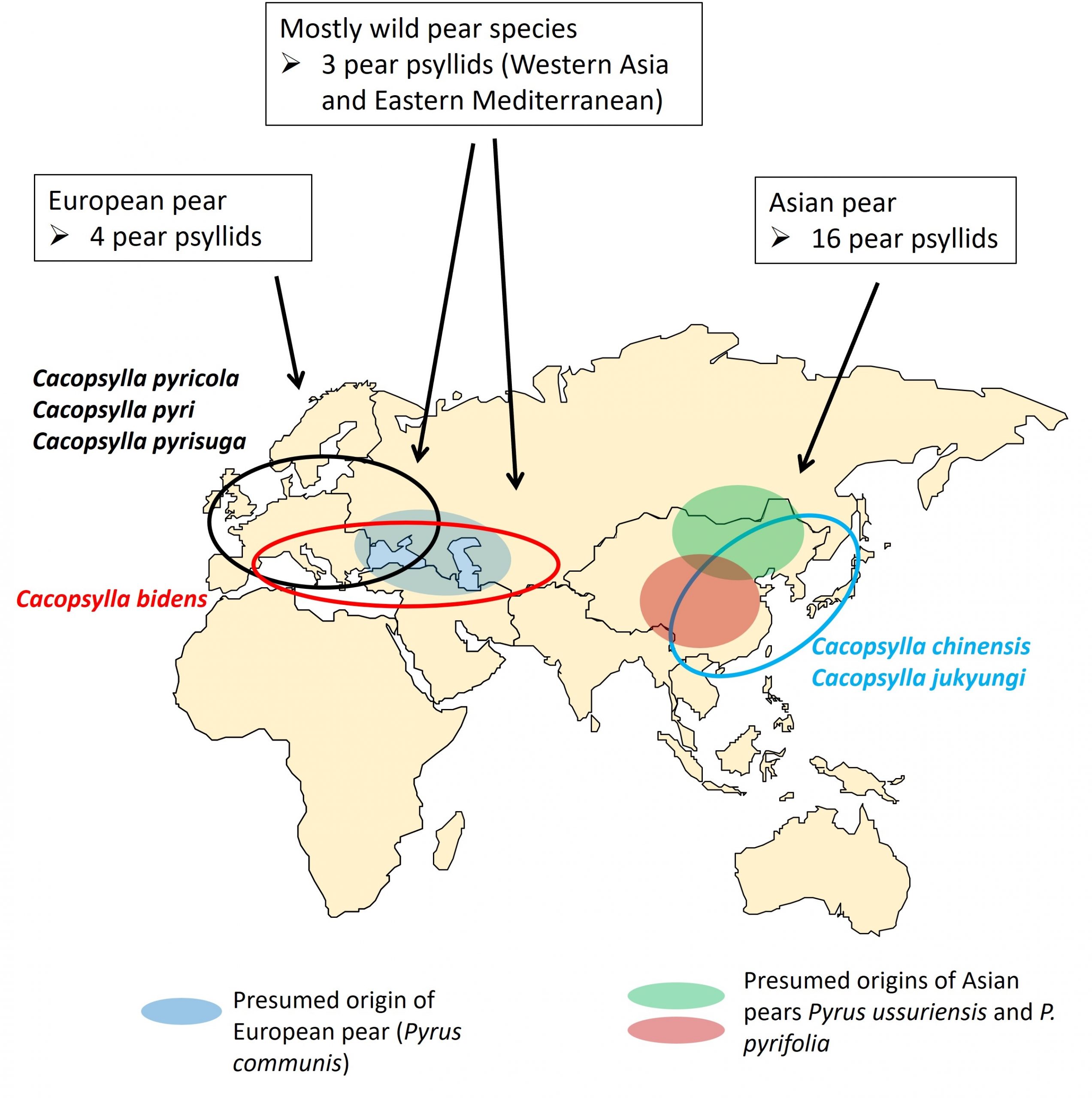

The psyllids are small, sap-feeding insects related to aphids, comprising more than 4,000 species and distributed in all regions except Antarctica. Individual species tend to be host-specific – thus, pear psyllids develop only on pears, willow psyllids on willows, and so forth. Consequently, geography of the host plant sets geography of its psyllids. Common domesticated pears are thought to have origins in two regions (shaded ovals in Fig. 1): the European pear (Pyrus communis) with origins in the Caucasus region; and two Asian pears (Pyrus ussuriensis, Pyrus pyrifolia) originating in China. Pyrus also includes more than two dozen wild species, with origins in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and temperate Asia. Human-assisted spread of pears through Europe and Asia began millennia ago. Spread of pears would have been accompanied by spread of the pear psyllids. The pear psyllid complex consists of 23 species that divide into three groups by geography and host plant (Fig. 1: boxes): four species on European pears in western and central Europe, with one of those species (C. bidens) extending into western Asia (Fig. 1: unfilled black and red ovals show rough limits of species); three species in western Asia/eastern Mediterranean on wild pear; and a group of 16 species on Asian pear, found from China into eastern Russia, Korea, and Japan. All species fall in the same genus as our North American pest (Cacopsylla). The primary pests of European pears are C. pyricola, C. pyri, and C. bidens. The most damaging pests of Asian pears are C. chinensis and C. jukyungi, with a combined range from Taiwan, through China, and into Korea and Japan (Fig. 1: unfilled blue oval).

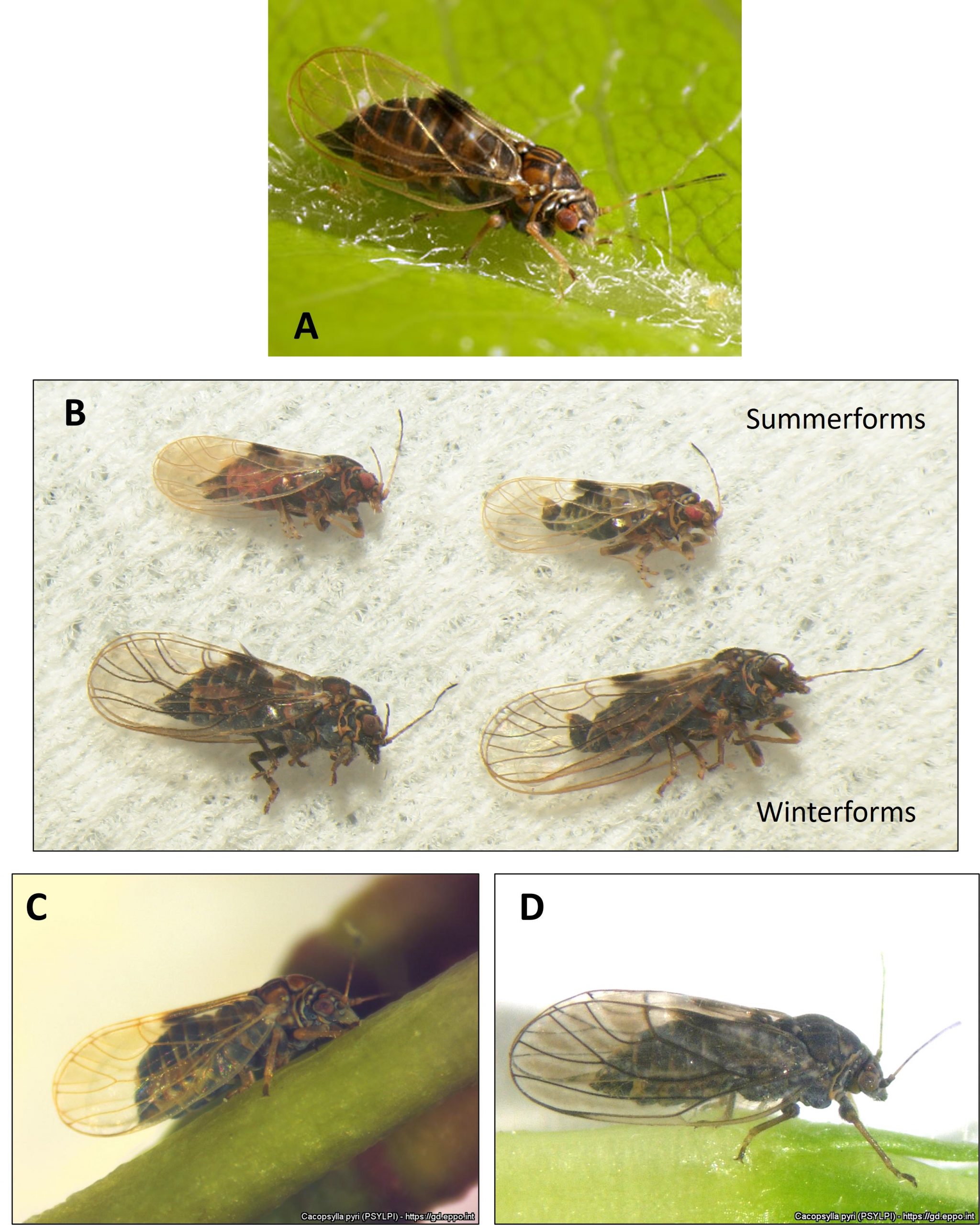

Several of the pear psyllids are very similar to C. pyricola in appearance and biology. External traits and life cycle of our pear psylla are likely to be familiar to North American growers (Figs. 2AB): adult insect about 1/8th inch in length, winter specimens (“winterforms”) larger than summer insects; reddish brown in summer, much darker in winter; life cycle of several generations each season.

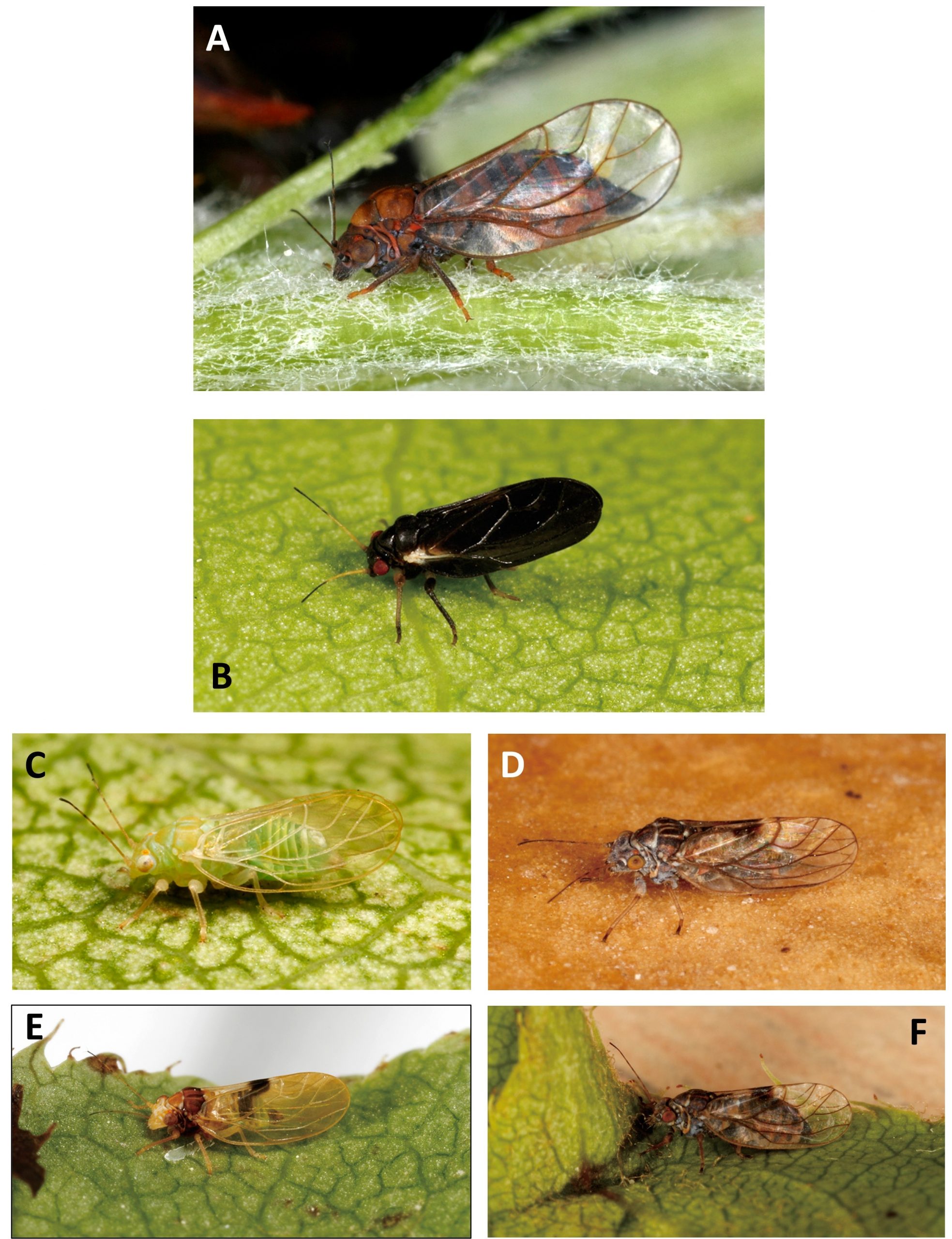

Two Western Europe species very similar to C. pyricola are C. pyri (Fig. 2CD) and C. bidens. Both are damaging pests. Both have the C. pyricola coloration, life cycle, and seasonal forms. Other pear psyllids, in contrast, are quite different from our species in color, size, or life cycle (Fig. 3). The European C. pyrisuga (Fig. 3A) – also known as the red or large pear psylla – co-occurs with C. pyricola and C. pyri throughout Europe (Fig. 1: unfilled black oval). This psyllid has a reddish hue, is very large (~1.2 to 1.3 times longer than our psyllid), and has but one generation per year. Several Asian species also are markedly unlike C. pyricola in appearance or life cycle. Cacopsylla nigella, found in China, Korea, and eastern Russia, is a striking black color with red eyes (Fig. 3B) and winters as immatures on the dormant pear tree. Other Asian species have the C. pyricola life cycle and its separate winter and summer forms even while not looking much like C. pyricola, such as Cacopsylla jukyungi (Figs. 3C [summerform] and 3D [winterform]) and Cacopsylla maculatili (Figs. 3E [summerform] and 3F [winterform]). Both species occur in China, Korea, and Japan on Pyrus ussuriensis.

“Pear Fever” Arrives in the Eastern US – and so does Pear Psylla

Why did we get Cacopsylla pyricola and how did it happen? Two factors came together in producing psylla’s early-1800’s arrival in the US – the Western Europe geography of C. pyricola, combined with an early-1800’s surge in importing of pear trees and scions from that same region.

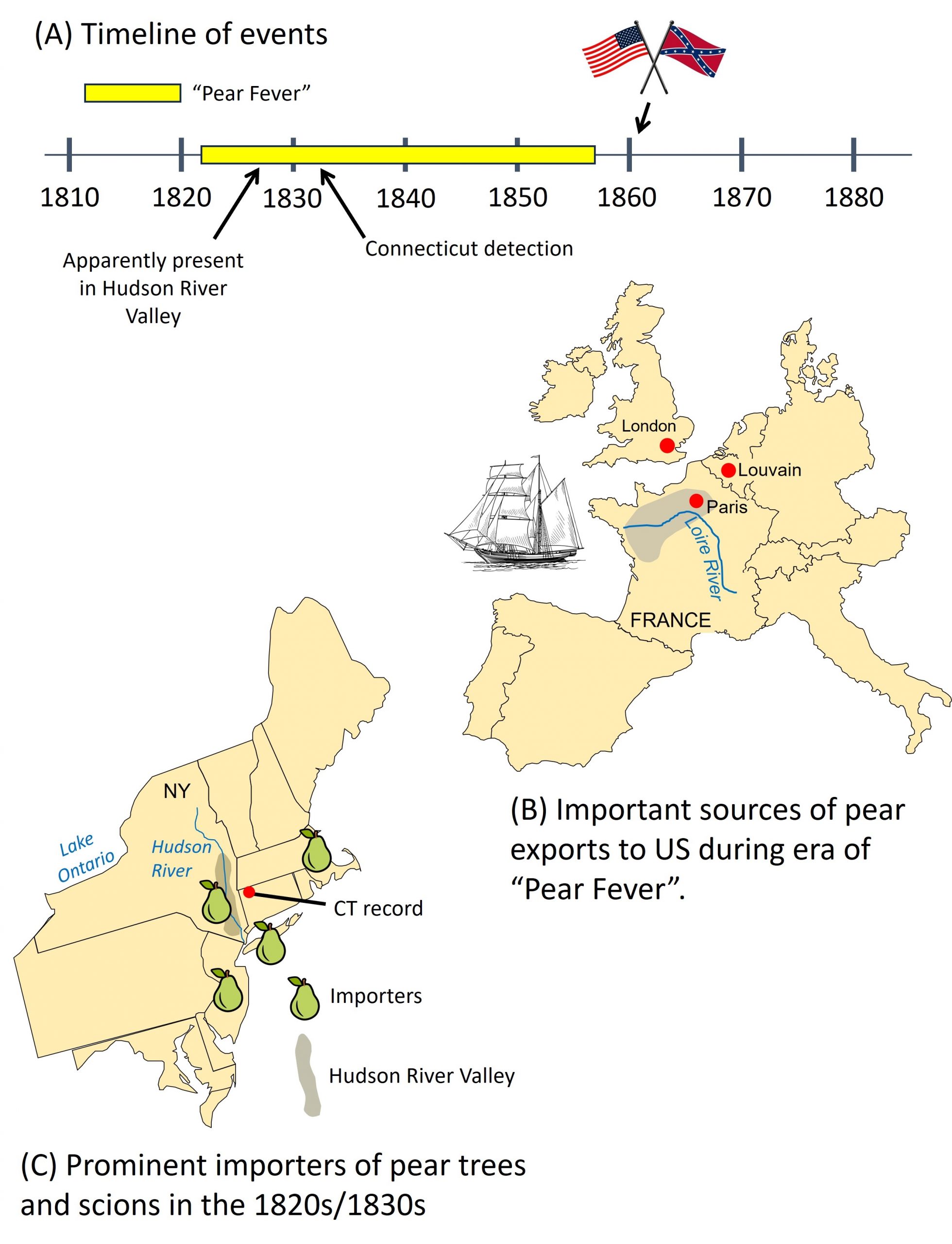

Pear psylla was first detected in the US during the autumn of 1832 at an orchard in Salisbury, Connecticut, although records of psylla-like damage to pear trees in the Hudson River Valley of New York during the 1820s strongly suggest that it was present before 1830 (Fig. 4A: timeline). It can be difficult today to appreciate just how long ago this was. When psylla was first detected in the US, the United States consisted of but 24 states extending only as far west as Missouri, the Civil War was still three decades into the future, Abraham Lincoln was only 23 years old, and the 1836 battle of the Alamo and death of Davy Crockett had yet to occur. Psylla entered the U.S. as a transatlantic hitchhiker on pear trees from Europe. At the time of entry, the infested trees would have arrived by sailing ship on a trip requiring one or two months.

Understanding where and when hitchhiking C. pyricola entered the US requires understanding the movements of pear trees and scions. Importing of pear cultivars into the US began in earnest in the 1820s at the onset of a 4-decade period known as “pear fever” having origins in Europe where it was likened to the tulip craze of the 1600s (Fig. 4A: yellow bar). New cultivars surged in the orchards of European pear breeders. Belgium, France, and England were the major sources of cultivars entering the eastern US when psylla arrived in the 1820s (Fig. 4B). Belgium may be the country most responsible for producing the modern pear – Belgium in fact was referred to as “the Eden of the pear tree” by one early-American pear grower. Many cultivars from Louvain, Belgium (Fig. 4B) in the early-1800s were sent to England and France for propagation and dissemination. Many also were exported to America. In France, Paris and its Royal Gardens were centers of pear culture in the seventeenth-century as the French aristocracy developed a passion for the fruit. Nurseries of the Loire River Valley and nearby regions (Fig. 4B) produced many cultivars that found their way into the US in the early 1800s. Lastly, while England was not a major producer of new cultivars, it was an important exporter of trees and scions to America. Cultivars from Belgium and France arrived regularly in the gardens of the Horticultural Society of London (Fig. 4B), followed often by dissemination to the US. The society catalog of 1826 listed more than 500 cultivars of pears in its London gardens, most of Belgian or French origin.

New England landowners and nurserymen of the early-1800s almost obsessively began to import these new cultivars, often with aims to collect and grow as many cultivars as possible. Prominent importers were found in three states (Fig. 4C: pear icons): New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. By the 1820s, American growers were receiving dozens of French and Belgian cultivars either directly from those two countries or from the Society gardens in London. One Massachusetts nurseryman (Robert Manning of Salem), for example, was growing over 500 cultivars by the 1840s, virtually all of French and Belgian origin. Psylla probably entered the US in the 1820s through one of these three states. The pest then spread rapidly: 1840s/1850s – much of the Hudson River Valley; 1870s – the Finger Lakes (Ithaca) region of NY; 1890 – upstate New York below Lake Ontario. By 1895 psylla had also entered Maryland, Massachusetts, Maine, New Jersey, Virginia, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Ontario, Canada. Explosive spread in the 1890s accompanied an outbreak of psylla in New York and dissemination of infested trees by New York nurseries. Psylla eventually made its way to the western US with its 1930s’ detection in eastern Washington State.

Conclusions

While the pool of pear psyllids in Europe and Asia is quite large – numbering over 20 species – a case can be made that North America managed to inherit the worst of the bunch: C. pyricola specializes on our standard commercial pear; it is well-suited to western US conditions; psylla’s multi-generation life cycle, high fecundity, and dispersal tendencies make the pest exceedingly invasive; and psylla has a long history of insecticide resistance. Pear psylla entered the eastern US in the early 1800s likely hitchhiking on pear trees or scions from western Europe (apparently Belgium, France, or England). Entry occurred during an era of “pear mania” when US pear enthusiasts began to import trees and scions in large numbers. Cacopsylla pyricola – along with the European pear psyllids C. pyri and C. pyrisuga – are the only species having the precise geography that would have produced opportunities for psyllids to hitchhike on these west European exports. Cacopsylla pyrisuga (Fig. 3A) is not invasive and is an unlikely hitchhiker: the species has but a single generation per year, with adults spending most of the year on non-pear shelter plants. This seems to leave the invasive C. pyricola and its sister species C. pyri as the only realistic choices for that 1820s/30s transatlantic crossing.

Contact

David Horton

USDA-ARS, Wapato, WA

david.horton@usda.gov

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Geonho Cho of Seoul University for generously allowing me to use his wonderful photographs of Asian pear psyllids. I also thank Rodney Cooper for reviewing an earlier version of this article.

Photo Credits

Fig. 2A (Cacopsylla pyricola): Brian Valentine https://www.britishbugs.org.uk/homoptera/Psylloidea/Psylla_pyricola.html. Fig. 2B (summer and winter forms of C. pyricola): Rodney Cooper, USDA-ARS, Wapato, WA. Fig. 2CD (Cacopsylla pyri): Monika Riedle-Bauer, Federal College and Research Institute for Viticulture and Pomology, Klosterneuburg, Austria; https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/PSYLPI/photos (open access). Figure 3A (Cacopsylla pyrisuga): Vladimir Motyčka; https://www.biolib.cz/en/image/id183554/ (used with permission). Figure 3B-F (Asian psyllids): Geonho Cho, Seoul University; https://mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.5177.1.1 (used with permission)

References Consulted

Pear psyllids diversity and geography

Burckhardt, D., and I.D. Hodkinson. 1986. A revision of the west Palaearctic pear psyllids (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 76: 119-132.

Cho, G., D. Burckhardt, H. Inoue, X. Luo, and S. Lee. 2017. Systematics of the east Palearctic pear psyllids (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) with particular focus on the Japanese and Korean fauna. Zootaxa 4362 (1): 075-098.

Cho, G., D. Burckhardt, and S. Lee. 2022. Check list of jumping plant-lice (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) of the Korean Peninsula. Zootaxa 5177 (1): 001-091.

Civolani, S., V. Soroker, W.R. Cooper, and D.R. Horton. 2023. Diversity, biology, and management of the pear psyllids: a global look. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 116: 331-357.

Pear history, diversity, and geography

Dondini, L., and S. Sansavini. 2012. European pear, pp. 369-413. In M.L. Badenes and D.H. Bryne (eds), Fruit breeding. Handbook of plant breeding 8, pp. 369-413. Springer, Boston, MA.

Morgan, J. 2015. The book of pears. Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT.

Silva, G.J., T.M. Souza, R.L. Barbieri, and A.C. de Oliveira. 2014. Origin, domestication, and dispersing of pear (Pyrus spp.). Advances in Agriculture 2014, 541097.

Arrival and spread of Cacopsylla pyricola in the eastern US

Slingerland, M.V. 1896. The pear psylla and the New York plum scale. Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 108: 69-86.

“Pear fever” and early American pomology

Hedrick, U.P. 1921. The pears of New York. New York Agric. Experiment Stn., Geneva, N.Y.

Hedrick, U.P. 1950. A history of horticulture in America to 1860. Oxford University Press, New York.

Manning, R., Jr. 1880. History of Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1879. Massachusetts Horticultural Society, Boston, MA.

Fruit Matters articles may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Reprint articles with permission must include: Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension Fruit Matters at treefruit.wsu.edu and a link to the original article.