Written by Achour Amiri, Washington State University, August 4, 2025

Background

Bins, whether wood or plastic, can serve as reservoirs for spores of pathogens that can infect fruit at harvest and during storage. Spores can spread to fruit through direct contact with bin surfaces, during fungicide drenching at harvest, or via air flow during long term storage. While spores of many fungi can survive on bins, those of Penicillium spp. and Mucor spp., which cause blue mold and Mucor rot, respectively, are of particular concern. Given the high number of bins circulating across Pacific Northwest orchards and packinghouses, thorough cleaning remains a labor-intensive and challenging task for growers and packers.

A semi-automated washer that can be transported between packinghouses and fields for high throughput bin cleaning

An outdoor automated bin washer developed by Packline Technologies Inc. (PTI), based in Fowler, CA, was evaluated near a commercial packinghouse in Washington State. The system uses high-pressure cold water from the packinghouse supply and can wash a set of 20 bins in approximately 5 minutes, averaging 20-25 seconds per bin (Figure 1). Each bin undergoes two wash cycles: first, a top to bottom rinse, followed by a second wash after the bin is flipped upside down and cleaned using a rotating spay system. During operation, the water is filtered through two sieves and recycled to conserve resources (Figure 1).

To evaluate the washer for spore removal, 20 visually clean bins (minor debris) and 20 visibly dirty bins (containing fruit mummies or smashed fruit residues) were swabbed pre- and post-washing. Peracetic acid (PAA) was applied at the label rate for 20 min before swabbing the same areas. Water samples from the packinghouse supply and after the first and second sieve-filters of the bin washer were collected to evaluate the presence of microorganisms.

Efficacy and Key Findings

Water Quality Findings:

- Water supply used at the packinghouse tested free of detectable microorganisms.

- The bin washer’s filtering system did not reduce microbial loads; post-filtration samples showed equal or higher microorganism levels than pre-filtration samples.

- While the system may remove sand or large debris, it does not effectively eliminate microorganisms, posing a risk of bin recontamination during the washing process.

Bin Contamination and Washing Effectiveness

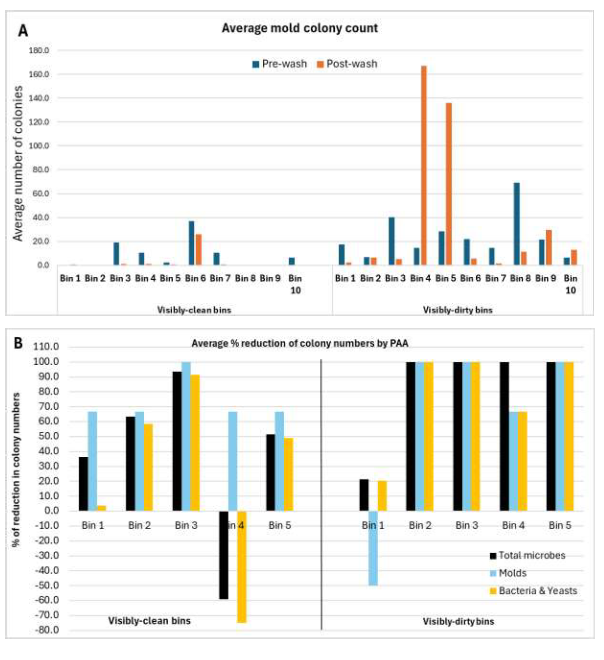

- Visually clean bins harbored fewer microorganisms than visually dirty bins pre and post-washing (Figure 2A).

- Visually dirty bins had significantly higher microbial loads and were less responsive to washing, with molds and other microbes remaining post-wash.

- In some cases, washing appeared to increase microbial levels, likely due to spread of residual rotten tissue or recontamination from recycled water.

A Sanitizer improves the efficacy of cleaning

- Application of PAA to washed bins improved microbial reduction on bin surfaces (Figure 2B).

- Except for one bin in each group, PAA significantly reduced microorganism counts, particularly molds in visually dirty bins, achieving reductions above 70%.

- These results emphasize the importance of sanitation (e.g., PAA application) in addition to mechanical washing for effective microbial control.

Conclusions

While the automated bin washer offers a high-throughput solution capable of washing thousands of bins per day, it also provides logistical flexibility, as it can be transported between sites to enable on-site bin cleaning near orchards—reducing both turnaround time and the risk of recontamination. Its ability to conserve water through recycling is an added advantage.

However, the system’s filtration mechanism requires significant improvement, as it currently fails to remove fungal spores, allowing them to persist and potentially recirculate during the washing process. Although high-pressure cold water helps remove surface residues, it alone is insufficient to eliminate microbial contamination, especially fungal spores.

Using hot water may enhance disinfection but may not be cost-effective. Therefore, integrating a sanitizing agent with the cold-water wash is recommended to achieve effective microbial control and spore elimination.

Contact

Achour Amiri

Washington State University

a.amiri@wsu.edu

509-393-4058

Fruit Matters articles may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Reprint articles with permission must include: Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension Fruit Matters at treefruit.wsu.edu and a link to the original article.

Use pesticides with care. Apply them only to plants, animals, or sites listed on the labels. When mixing and applying pesticides, follow all label precautions to protect yourself and others around you. It is a violation of the law to disregard label directions. If pesticides are spilled on skin or clothing, remove clothing and wash skin thoroughly. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

YOU ARE REQUIRED BY LAW TO FOLLOW THE LABEL. It is a legal document. Always read the label before using any pesticide. You, the grower, are responsible for safe pesticide use. Trade (brand) names are provided for your reference only. No discrimination is intended, and other pesticides with the same active ingredient may be suitable. No endorsement is implied.