Written by Louis Nottingham, PhD, WSU Entomology, TFREC. May 2018.

In most regions of Washington, the first generation of pear psylla nymphs have completed development, giving way to the first round of summerform adults. Summerforms will mate, lay eggs and disperse over the next few weeks or longer. A major challenge to managing the second generation of psylla is the diminishing congruence among life-stages. Summerform adults will continue to lay eggs for multiple weeks, breaking the uniformity often seen in the first generation. Regardless of the current psylla severity in a given orchard, adults are capable of immigrating from other orchards, rendering new generations with overlapping life-stages.

Management at this point in the season can be ambiguous. On one hand, it is important to stay vigilant because there is a still plenty of time for a clean orchard to become infested. On the other hand, over-spraying can eliminate important natural enemies (predators and parasitoids), accelerate insecticide resistance, and squander stronger products that may be more necessary later in the season. So how do we stay vigilant on the current psylla population, while conserving natural enemies and avoiding overuse of insecticides?

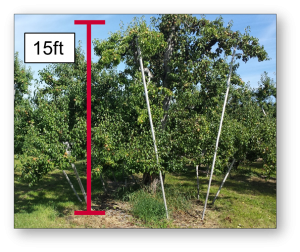

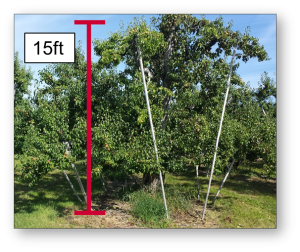

We first have to recognize that the success of a spray program is only as good as the coverage. Pears (especially Anjous) exhibit high rates of vegetative growth from late spring through mid-summer, which not only inhibits spray penetration, but also increases the overall area requiring insecticide coverage. Additionally, summerform adults target new vegetative growth for egg laying because these zones are rich in mobile nutrients and low in physiological defenses. For these reasons, it is important to manage excessive vegetative growth.

While it is tempting to give our trees as much food as possible, over-fertilizing will likely do more harm than good. Only supply enough nitrogen fertilizer to achieve adequate fruit set and size. Pruning new vegetative shoots (water sprouts and suckers) is also important. Not only will this promote better coverage, but it removes prime psylla habitat. Pull shoots by hand instead of using loppers to minimize regrowth. Thinning should be performed prior to shoots developing woody attachments to limbs, before the end of June.

Choosing which insecticides to spray when the psylla population is low can be tricky. It seems hard to justify spraying at all, but even very low pest densities can rapidly turn a good situation bad. For this situation, selective materials like the insect growth regulators (IGRs) pyriproxyfen (Esteem), buprofezin (Centaur) and organic azadirachtin (Aza-Direct and Neemix) may be the best options for prophylactic psylla management. Their effects are less dramatic than broad spectrum materials, which is good for insecticide resistance prevention and conservation of natural enemies. Frequent tank mixed sprays (around 7-day intervals) of multiple selective materials can suppress the current population, and protect against invaders and late hatches. This method also saves stronger materials for later in the season if psylla populations increase above thresholds.

Kaolin clay (Surround) may be a useful addition to selective, late-spring sprays. This material is used frequently prior to bloom to repel overwintered psylla adults and inhibit oviposition, but it is often overlooked after leaves appear. Summer insecticides are mainly effective on nymphs but do little to mitigate the nearly continuous activity of adults. Adding kaolin to a summer insecticide sprays is likely to provide greater control longevity by both repelling immigrating adults and inhibiting oviposition by the adults already in the orchard. Additionally, kaolin reduces nymph survivorship by interfering with their ability to maneuver and remain attached to plant tissue.

Plant defense elicitors (PDEs), such as Actigard and Employ, can provide subtle improvements to insect and disease management by increasing trees’ physiological defenses. PDEs are more commonly applied for the suppression of plant diseases like fire blight, but recent studies have shown that these products can lead to measurable reductions in psylla populations. Fire blight has been a growing problem in many orchards, and 2018 has been especially severe due to high temperatures and wetting events during bloom. Growers that are considering the use of PDEs to suppress blight should keep in mind that these products can reduce survivorship of psylla as well.

Late spring is an excellent time to implement these softer management strategies for psylla. Saving harsher insecticides for later in the summer gives predator populations time to build (which, in theory, could prevent the eventual need for harsher insecticides) and it helps slow the rate of insecticide resistance. However, it is important to be patient and somewhat cautious when trying soft tactics, as there is no concrete recipe for success. Every orchard is different, and some approaches may work in one situation and not in another. Transitioning orchards may take multiple years before natural enemies fully recolonize. These orchards may see psylla populations increase above threshold for the first couple years under soft programs, because there simply aren’t many predators and parasitoids in the area to come to the rescue.

When implementing programs, the following principles should be considered:

- Coverage is key: remove new shoots to gain better coverage and reduce psylla habitat.

- It’s better to spray frequently with multiple selective materials than infrequently with strong materials. Softer materials have more subtle effects, so they need to be combined and repeated to suppress an aggressive pest like pear psylla.

- Coordinate management programs over larger areas so sprays or other tactics occur on the same schedule. Get neighbors involved if possible. This will reduce psylla movement between orchard blocks.

- Have a bail-out plan like tree washing. Soft programs notoriously struggle when first implemented because it can take multiple years before predators and parasitoids rebound. Luckily, honeydew is just sugar water, so it washes away easily. Tree washing can be performed by spraying high water volumes from an airblast sprayer, or more easily with overhead sprinklers. Remember, too much water at the wrong time can stimulate diseases like fire blight. Only wash later in the season when fire blight risk is low. When using overheads, the goal is to achieve dripping leaves throughout the canopy for about 1-3 hours (depending on tree size).

Contact

Postdoctoral Research Associate, Washington State University

Tree Fruit Research & Extension Center

1100 N Western Ave., Wenatchee, WA 98801

Use pesticides with care. Apply them only to plants, animals, or sites listed on the labels. When mixing and applying pesticides, follow all label precautions to protect yourself and others around you. It is a violation of the law to disregard label directions. If pesticides are spilled on skin or clothing, remove clothing and wash skin thoroughly. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

YOU ARE REQUIRED BY LAW TO FOLLOW THE LABEL. It is a legal document. Always read the label before using any pesticide. You, the grower, are responsible for safe pesticide use. Trade (brand) names are provided for your reference only. No discrimination is intended, and other pesticides with the same active ingredient may be suitable. No endorsement is implied.

Fruit Matters articles may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Republished articles with permission must include: “Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension Fruit Matters at treefruit.wsu.edu” along with author(s) name, and a link to the original article.