Information from Dr. Ken Eastwell, Plant Health Specialties; summarized by Tianna DuPont, WSU Tree Fruit Extension. April, 2017.

With the concern around little cherry disease, growers are testing and finding a number of other cherry viruses in their orchards. Dr. Ken Eastwell spoke about Western X and cherry viruses at this year’s WSU Extension Fruit Days in Wenatchee. Here are some highlights.

While viruses do not always kill your trees right away, they are all robbing your trees of energy. This impacts yield and sometimes fruit quality. Although Little Cherry virus 2 was the most common pathogen associated with little cherry disease in recent tests, Western X was also frequently found. In a recent survey, Little Cherry virus 1 was found infrequently and occurred only in combination with other agents associated with little cherry disease. Many other viruses were also found.

Western X Phytoplasma

Western X is not a virus. It is a special type of bacteria called a phytoplasma. The Western X phytoplasma lives in the vascular system of the tree and clogs the system, blocking movement of water and nutrients. Symptoms often include irregular fruit ripening. In the same cluster, you can have normal fruit right next to fruit that is not the right size or color. In contrast to the effects of Little Cherry virus 2 where fruit often has little flavor, fruit from Western X-infected trees generally have a bitter taste. In addition to fruit symptoms you will see reduced growth and extension of infected limbs, sometimes leading to crowding of leaves into dense clusters (called a rosette). The first infected trees in an orchard usually occur within one or two trees from the edge of orchard blocks, and frequently adjacent to sagebrush or steppe grassland areas. Secondary spread to trees further in the block continues from these initial infection sites.

The Western X phytoplasma replicates in the phloem tissue of the tree. It has an interesting life cycle. It is believed that the phytoplasma dies in the aerial parts of the tree as the branches go dormant during the winter months, but living phytoplasma overwinters in the roots. In the spring, the aerial portions of the tree become re-infected as the phytoplasma moves up the phloem of the tree, usually following the same general route as in the previous year. As a result, you may see symptoms in one limb for a year or more, but symptoms will eventually appear in additional limbs. Removing a symptomatic limb does not eliminate the phytoplasma since it is already in the root system before symptoms appear.

Leafhoppers are the vector for Western X. Once a leafhopper is infected, they are infected for life. There are two leafhopper species (Colladonus reductus and C. geminatus) that are the most prevalent in Washington orchards and that carry the Western X phytoplasma. In one survey, 33% to 36% of these leafhoppers were carrying the Western X phytoplasma. C. geminatus infected with Western X is most likely found early in the season (late April and early May), whereas C. reductus with Western X is usually found later in the season (late July and early August). Further studies are in progress to follow populations of infected leafhoppers later in the season, and to verify their ability to transmit the phytoplasma.

Western X is not a new problem. It was first identified in cherry trees of WA State in 1946. In a 1947 survey, about 1% of cherry trees were infected. Testing for Western X became possible beginning 20 years ago when a laboratory assay was developed based on conserved regions of the genome. Since then, tests have improved significantly, and currently, regions of DNA unique to Western X have been identified that can be used in various laboratory assay systems. Major improvements were made to the assay system in 2015, and again in 2016, and will likely continue every year as more data is gathered.

Sampling: There is a wide range of samples types and times when they can be taken. Sample either:

- Leaves from older wood: 2 months post bloom

- Green shoots: after fruit harvest

- Bark: anytime (1 month post bloom is better)

- Flower stems: anytime fresh tissue available

- Flower petals: anytime fresh tissue available

- Fruit stems: anytime fresh tissue available

Contact your preferred diagnostic laboratory to coordinate testing. This is important so samples can be tested as soon as they are submitted and while still fresh.

Recommendations for management of Western X:

- Start with clean planting stock.

- Survey and mark symptomatic limbs for testing a week before harvest.

- Return after harvest to collect samples.

- Don’t forget to look in and sample nearby abandoned blocks.

- Remove infected trees.

- Manage the leafhopper vector.

Removal of infected trees is important: In an early study, orchards where infected trees were removed as soon as they were observed, the disease incidence remained below 2% and decreased over time. Orchards where growers left infected trees as long as they were able to harvest some fruit experienced a dramatic rise in the incidence of diseased trees. It may be heartbreaking, but be aggressive and remove infected trees. Infected trees are a source of the disease that will spread through the remainder of the block by leafhoppers.

To manage leafhoppers: Avoid indiscriminant sprays. Target the early and late season. It helps to identify which leafhopper you have present so that you can eliminate one spray if possible. Manage alternative hosts of the phytoplasma and of the leafhoppers – clovers, dandelions, curly dock, bitter cherry, chokecherry. Broad leaf weeds are difficult to eliminate from an orchard but by suppressing them, your orchard becomes less attractive to the leafhopper vectors.

Cherry Leaf Roll Virus

First detected in Washington in 1997, new Cherry leaf roll virus infections are found every year. Symptoms include late ripening (3 to 10 days depending on weather) and poor color. If trees are infected with additional viruses, symptoms may include outgrowths (enations) on the underside of the leaves. Virus distribution in the tree is erratic, and as such, it is critical to only test limbs that are symptomatic. Cherry leaf roll virus is transmitted by budding, grafting, and root grafting. It can also be transmitted by pollen to seedlings, which is important if you are using seedling rootstock. It is believed that it can be transmitted by pollen to the pollen recipients at a low frequency. If trees are removed immediately after you see first see symptoms, it is reasonably easy to eliminate this virus from your orchard. But if you wait until multiple trees become infected, then control becomes very difficult.

Cherry Raspleaf Virus

Cherry raspleaf virus’s most characteristic symptoms are pronounced enations on the leaves of lower limbs. It reduces growth and fruit production, and causes flattened fruit in both cherry and apple. Cherry raspleaf virus can move into an orchard on infected plant material. The primary vector of the virus is dagger nematode (Xiphenema species), a plant feeding nematode. Cultivation and other movement of soil containing infected nematodes can move it through an orchard, or from orchard to orchard. Dandelions and the native blue elderberry are also hosts of Cherry raspleaf virus. Seeds from infected plants have the potential to move the virus to new areas.

Rusty Mottle

The rusty mottle group is a diverse collection of viruses. Little is known about these viruses including how they spread, other than by the use of infected planting stock. The foliar symptoms can be quite diverse but all reduce tree yield. All the viruses in this group cause late fruit ripening and reduced fruit quality.

Cherry Mottle Leaf

Dappled leaves are the principal symptom of Cherry mottle leaf virus; severe strains also cause strap-like leaves to develop. The virus retards tree growth, and when severe, the fruit can lack flavor and ripen later. Cherry mottle leaf virus is transmitted by budding, grafting and microscopic eriophyid mites. These mites carrying the virus are carried on clothing and by wind currents, often invading orchards along the edge of canyons from bitter cherry, their native host.

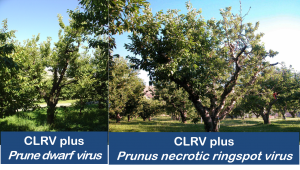

Prunus Necrotic Ringspot Virus (PNRSV) and Prune Dwarf Virus (PDV)

Since these viruses are pollen transmitted, they are relatively common in older orchards of WA State. Nevertheless, their greatest impact is on the growth of young trees, so starting with clean planting stock is important even if the trees may become infected later in their productive life. There are circumstances where these viruses cause significant damage. Some strains of PNRSV interact with gibberellic applications to cause a disease referred to as ugly fruit. This scarring is particularly evident on light fleshed cherries. The disease can be managed by reducing the concentration of gibberellic acid sprays or by the timing of the sprays. Symptoms of PNRSV and PDV can vary, sometimes appearing as necrotic spots that develop into shot-holes or rugose mosaic. These viruses also interact with other viruses that may be present, and generally make disease development much more severe.

Many of the new hybrid rootstocks being developed for the cherry industry are hypersensitive to one or both of these viruses. In these cases, if a tree becomes infected, trees will die at the graft union. This isn’t necessarily a bad result as it eliminates source of virus spread. Do your homework! Learn the characteristics of any rootstock that you consider and the possible consequences. Determine the virus pressure in your particular orchard.

Basic Virus Management Strategies

- Plant virus-tested trees.

- Identify the pathogen so you can learn its biology.

- Reduce vector populations as appropriate.

- Reduce sources of infection: from orchard trees, weeds, native vegetation inside and outside the orchard.

- Alter orchard management to reduce impact.

- Examples:

- Reduce concentration of gibberellic acid to reduce ugly fruit.

- Don’t cultivate orchards with nematode-transmitted viruses.

- Reduce broad leaf weeds that act as reservoirs of viruses and vectors.

- Examples:

- Tree removal

- Pathogens exist in roots, therefore:

- Apply a systemic herbicide to freshly cut stumps to kill the root system and identify adjacent trees that may be infected through root grafting.

- TIP: apply herbicide to stumps of symptomatic trees ONLY.

- Carefully remove as much root material as possible.

- Leave the vacant spot fallow for 1 year if possible, and treat any suckers/seedlings that emerge with herbicide.

Virus testing at Clean Plant Center Northwest, Washington State University-IAREC, Prosser

Contact information:

Call the laboratory before collecting and shipping samples, to ensure that the samples can be analyzed and that the samples are expected.

PCR testing laboratory: 509-786-9372

ELISA laboratory: 509-786-9382

Shipping instructions:

- Include a packing list that clearly indicates the specific tests being requested, billing information and contact information in case questions arise about the tests. Ship by overnight express to:

Clean Plant Center Northwest – PCR/ELISA lab

WSU– IAREC, 24106 North Bunn Road

Prosser, WA 99350

Telephone: 509-786-9372 or 206-786-9382

- Ship early in the week (Monday through Wednesday) so that the samples are not stranded over the weekend. In extremely hot weather, it is best to ship the samples in an insulated container with ice packs (but do not allow leaves to contact the ice pack directly – they will freeze).

Resources for more Information

Field Guide to Sweet Cherry Diseases in Washington

Contacts

Plant Health Specialties

WSU Extension Specialist, Tree Fruit

tianna.dupont@wsu.edu

(509) 663-8181 ext 211