by Elizabeth H. Beers, George N. Oldfiield, and Peter H. Westigard, originally published 1993

Aculus schlechtendali (Nalepa) (Acari: Eriophyidae)

The apple rust mite has been studied both as a pest and a beneficial arthropod. Although it can damage fruit and foliage of apple, its major role in Pacific Northwest orchards is as an alternate food source for predatory mites. It is found throughout the apple growing regions of the United States, Canada, Europe and Australia.

Hosts

The apple rust mite attacks cultivated apple and several other species in the genus Malus. It can also survive and reproduce on pear and has been found in mixed populations with the pear rust mite.

Life stages

Egg

The egg is about 50 microns in diameter and 30 microns high. It is initially clear but becomes translucent as the embryo matures.

Immatures

The first nymphal stage is white, about 68 microns long, increasing to 104 microns before molting. The quiescent stage is immobile and the cuticle is shiny, later turning to tan. The second instar nymph is a pale tan and 104 to 124 microns long. This stage also goes into a quiescent stage before molting.

Adult

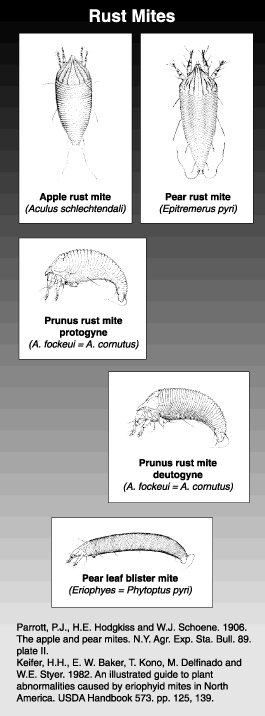

The adult is medium tan in color, becoming darker with age. Protogyne females are 166 to 181 microns long, slightly larger than the males (see section Biology of Tree Fruit Rust Mites).

Life history

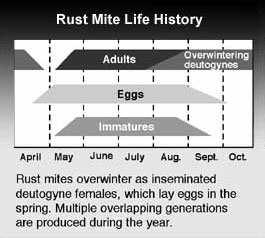

The species overwinters as deutogynes (females) in crevices on twigs and under bud scales. Often large clusters can be found under a single scale. They emerge to feed principally on the undersurfaces of leaves as the buds begin to open in the spring. They lay eggs that hatch into immature mites which rapidly grow through two instars. There are several generations per growing season. Development is more rapid in warm temperatures. In one study, a generation took 39 days to develop at 50°F but only 10 days at 72°F. The lower developmental threshold is between 39 and 45°F. Overwintering forms can be produced as early as mid-July if foliage condition is poor, but by fall only overwintering forms remain. They seek sheltered sites to spend the winter.

The species overwinters as deutogynes (females) in crevices on twigs and under bud scales. Often large clusters can be found under a single scale. They emerge to feed principally on the undersurfaces of leaves as the buds begin to open in the spring. They lay eggs that hatch into immature mites which rapidly grow through two instars. There are several generations per growing season. Development is more rapid in warm temperatures. In one study, a generation took 39 days to develop at 50°F but only 10 days at 72°F. The lower developmental threshold is between 39 and 45°F. Overwintering forms can be produced as early as mid-July if foliage condition is poor, but by fall only overwintering forms remain. They seek sheltered sites to spend the winter.

In cooler climates, apple rust mite populations peak once in midsummer. In hot, dry climates, populations peak in early summer and again in fall, with the midsummer decline corresponding to temperatures above 95°F (35°C) and relative humidities below 20%.

Damage

Apple rust mite inserts its mouthparts into plant cells and sucks up their liquid contents. This feeding produces a silvery cast to the leaf in the early stages which tends to get browner as the season progresses. Bronzing caused by apple rust mite is more finely textured than spider mite bronzing and lacks the stippling produced by spider mites. Rust mite damage sometimes causes leaves to roll lengthwise.

Like other pests that affect the foliage, damage disrupts photosynthesis and the trees’ water balance. Excessive amounts of damage, with peak populations greater than 300 mites per leaf or 4,800 mite days, can reduce fruit growth. Populations in excess of 2,000 per leaf have been noted.

As well as affecting fruit size, rust mite feeding can cause premature terminal bud set. Depending on the overall vigor of the orchard and other cultural factors, this may not be a problem.

Rust mites can also feed directly on the skin of fruit, causing a tan russeting. Usually this feeding is concentrated around the calyx end. This is only a problem on light colored cultivars such as Golden Delicious.

Monitoring

The presence of large numbers of rust mites can be detected by the color of the leaves. Such detection can be confirmed with a hand lens of 10-power magnification or greater. If an estimate of the population is needed, the brushed leaf samples taken to monitor spider mites (see Monitoring under European red mite) can also be used for this. Because of their size, an even smaller fraction of the glass plate is counted, usually 1/10th to 1/20th. It is often helpful to make counts of plates in two stages: first, for all stages of spider mites and predatory mites; and then, using a higher magnification, for the rust mites. This allows the eye to readjust to their smaller size.

Biological control

The predatory mites Typhlodromus occidentalis and Zetzellia mali attack apple rust mites but generally do not control them. Predators can increase their numbers early in the season by feeding on apple rust mites, thus providing better control of spider mite populations that develop later.

Management

Control measures for rust mites as foliage feeders are rarely called for. Populations of up to 50 mites per leaf in May or 250 in late June do not warrant control. Even if populations exceed 300 per leaf, the benefit of having them as an alternate food source for predatory mites must be weighed against the possibility of yield loss. An added benefit of rust mites is that their feeding preconditions foliage so that it is less suitable for build-up of the more damaging spider mites.

The time of year and weather should also be factored into rust mite control decisions. Because of the tendency of rust mite populations to drop sharply during hot weather in July and August, control measures applied just prior to this period could be wasted. Consider control only where rust mite populations remain high into July and there are no predatory mites. Make sure that trees are adequately irrigated during this period so they are not subject to water stress, which would exacerbate the effects caused by the mites’ feeding. An exception to the above strategy is in the case of high levels of rust mites prebloom on Golden Delicious. If populations are high, then control to prevent fruit damage is warranted. Chemical controls will be most effective at about the pink stage of blossom development.

Materials available for apple

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Biology of tree fruit rust mites

Life stages

Eggs: Rust mite eggs are extremely small, roughly hemispherical, and require 100-power or greater magnification to be seen.

Eggs: Rust mite eggs are extremely small, roughly hemispherical, and require 100-power or greater magnification to be seen.

Immatures: Rust mites have two nymphal instars. All stages of immatures and adults have two pairs of legs at the front end of the body, and an elongate abdomen (hystersoma) with many striations appearing as rings. This appearance is referred to as annulate.

Adults: Adult females occur in two forms: deutogynes and protogynes. Deutogynes are a special form of female that overwinters. The differences between these two forms make species identification difficult. Protogynes are the normal females, which occur throughout much of the growing season and reproduced immediately upon becoming adults. These are the forms on which species identifications are usually based. Males also occur in the species that attack tree fruits, but do not overwinter. They are slightly smaller but are similar in appearance to the protogynes.

Life history

Rust mites overwinter as inseminated deutogynes. These females do not reproduce in the year in which they are produced. Some chilling is required before they will lay eggs in the spring. As with protogynes, these eggs produce both males and females. The rust mite has two nymphal instars, which resemble the adult but are smaller. Each molt is preceded by a quiescent phase. Male rust mites are produced by unfertilized eggs and females are produced by fertilized eggs (arrhenotokous parthenogenesis). They do not actually mate. The males deposit stalked spermatophores (structures containing a packet of sperm) on the leaves. Females walk over a spermatophore and empty it of the sperm, storing it in a special pouch called a spermatheca. Both sexes will be produced from eggs when females have access to spermatophores. Multiple overlapping generations are produced during the year, the number depending on the climate, location and condition of the host. The hibernating forms (deutogynes) are produced in response to either poor host condition or climatic conditions (cool weather, shorter photoperiod) that occur in the fall.