by A. L. Antonelli and Stanley C. Hoyt, originally published 1993; revised July 2019 Robert J. Orpet.

Forficula auricularia Linnaeus (Dermaptera: Forficulidae)

The European earwig, native to Europe, arrived on both coasts of the United States in the early 1900s. It is now found in temperate and Mediterranean areas worldwide and is the most common earwig species found in Pacific Northwest orchards. European earwig often damages stone fruits, but rarely damages pome fruits. However, it is often seen sheltering in or feeding in splitting fruit and wounds originating from mechanical or other insect damage. The name earwig comes from an old, unfounded superstition that the insect invades the ears of humans. Earwigs are nocturnal and feed at night. During the day they will hide under leaves, inside leaves rolled by leafrollers, in refuse on the ground, under loose bark, or in crevices on the tree trunks. When disturbed they move about quickly looking for new hiding places.

Hosts

Earwigs are omnivores capable of feeding on a wide range of plants, animals, and fungi. Plants consumed include grass, vegetables, flowers, tree fruits, berries, ornamental trees and shrubs, and moss. Aphids are favored prey. Caterpillars and eggs from a range of insects, including codling moth and other Lepidopteran pests are also consumed. At times, earwigs can be scavengers and feed on decaying vegetation or dead insects.

Life stages

Egg

The egg is small, oval and pearly white. They occur in clutches of 30–60 in underground nests found from fall to spring.

Nymph

There are four instars in European earwig. Nymphs look like adults except wingless. They have forceps-like appendages at the rear (pincers), and these are smaller and straighter than those of adults. Freshly molted earwigs start out creamy white but the cuticle soon hardens and darkens in color.

Adult

The adult European earwig is brownish-black and about 3/4 inch (2 cm) long ( including their pincers). The male has curved forceps and the female’s are straight. It has short, leathery forewings under which are tucked a rear pair of wings that look like tiny fans when open, but it rarely flies. European earwigs have scent glands on their abdomen that release a foul-smelling odor, which is probably for defense.

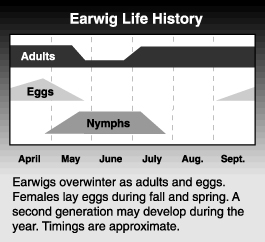

Life history

European earwig has one generation per year. In the fall, adults form earthen cells in the soil in which they live in pairs. The females lay eggs in these cells during the fall and spring. The cells containing the eggs are in the top 2 to 3 inches of soil. In the spring, the females open the cells and first instars will forage at night, returning to the nest during the day. Earwigs are subsocial and mothers look after their young in the early stages by collecting extra food to provision the nest and by protecting the nest from invaders. Nymphs eventually abandon their nest during their first or second instar to live independently on the ground. In the Pacific Northwest, some adult females will construct a new nest and lay a second clutch of eggs at this time. During the third instar, nymphs begin to spend most of their time in plant canopies instead of on the ground. They will continue to forage mainly in plant canopies through adulthood until constructing a nest in the fall.

European earwig has one generation per year. In the fall, adults form earthen cells in the soil in which they live in pairs. The females lay eggs in these cells during the fall and spring. The cells containing the eggs are in the top 2 to 3 inches of soil. In the spring, the females open the cells and first instars will forage at night, returning to the nest during the day. Earwigs are subsocial and mothers look after their young in the early stages by collecting extra food to provision the nest and by protecting the nest from invaders. Nymphs eventually abandon their nest during their first or second instar to live independently on the ground. In the Pacific Northwest, some adult females will construct a new nest and lay a second clutch of eggs at this time. During the third instar, nymphs begin to spend most of their time in plant canopies instead of on the ground. They will continue to forage mainly in plant canopies through adulthood until constructing a nest in the fall.

As earwigs rarely fly and tend not to crawl long distances, infestations in orchards spread slowly.

Damage

Earwigs can damage both leaves and fruit. Leaf damage is unsightly but of little concern on mature trees. On young seedlings, however, the earwig’s feeding on shoot tips can stunt tree growth. Damage on tree fruit crops is usually confined to shallow areas on the surface, irregular in shape but with rounded edges. Occasionally an earwig will bore through and feed on the flesh near the pit of stone fruits. Earwigs will get into any area damaged by other pests, such as birds and caterpillars. On apples, they are often found in stem bowl splits, which they can feed in and expand, creating the false impression that the earwig may have caused the initial damage. Recent studies have failed to find evidence that earwigs increase damage to apples in commercial Gala and Fuji orchards. However, softer-flesh and open-calyx apple varieties may be more vulnerable to attack by earwigs.

Beneficial role

The European earwig is an important predator of some fruit pests, with aphids, pear psylla, mites, and insect eggs (including those of codling moth) forming a significant part of the diet. European earwigs contribute considerably to woolly apple aphid and pear psylla suppression and may have a role in suppressing a range of soft-bodied pests.

Monitoring

Earwigs are attracted to tight hiding spots during the day where they can occur in large numbers due to their aggregation pheromone. If you provide a hiding place such as corrugated cardboard or deep pile carpet (with the pile toward the inside) on tree trunks or branches, the earwigs will gather there. Large numbers may also be trapped in boxes that are filled with straw or newspapers and inverted on the ground, or under flat boards laid on bare ground. Late instars and adults will be found at peak abundance in tree canopies in early July, making this the best time to monitor earwigs using shelters placed in trees.

Management

Whether managing earwigs to suppress them or conserve them, timing of management tactics is important. While nesting (from ca. October to April), earwig populations can be harmed by tillage disturbing the soil to depths of over 3 inches. When early instars are foraging on the ground (from ca. April to June), populations can be suppressed by insecticidal baits applied on the orchard floor. While later instars and adults are foraging in trees (from ca. June to October), insecticide sprays can suppress them. Spraying during the first half of the night after sunset will result in the greatest suppression because this is when European earwigs are most active. During the day, earwigs may be sheltered from sprays in their hiding spots under bark and other tight spaces. Lastly, European earwigs can be almost completely prevented from entering fruit tree canopies by placing sticky bands around the base of trunks.

Earwig Gallery

Earwig in Action

References

Berenbaum, M.R. 2007. Lend me your earwigs. American Entomologist 53(4): 196–197.

Crumb, S.E., P.M. Eide, A.E. Bonn. 1941. The European earwig. USDA Technical Bulletin No. 766:76

Moerkens, R., H. Leirs, G. Peusens, and B. Gobin. 2010. Dispersal of single- and double-brooded populations of the European earwig, Forficula auricularia:a mark-recapture experiment. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 137(1):19–27.

Nicholas, A., R. Spooner-Hart, and R. Vickers. 2004. Susceptibility of eight apple varieties to damage by Forficula auriculariaL. (Dermaptera: Forficulidae), an effective predator of Eriosoma lanigerumHausmann (Hemiptera: Aphididae). General and Applied Entomology: The Journal of the Entomological Society of New South Wales 33:21–24.

Lamb, R.J., and W.G. Wellington. 1975. Life history and population characteristics of the European earwig, Forficula auricularia L. (Dermaptera: Forficulidae) at Vancouver, British Columbia. The Canadian Entomologist 107:819–824.

Orpet, R.J., J.R. Goldberger, D.W. Crowder, and V.P. Jones. 2019. Field evidence and grower perception on the roles of an omnivore, European earwig, in apple orchards. Biological Control 132:189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.02.011

Orpet, R.J., D.W. Crowder, and V.P. Jones. 2019. Biology and management of European earwig in orchards and vineyards. Journal of Integrated Pest Management 10(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmz019

Articles from the Tree Fruit website may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Reprint articles with permission must include: Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension Fruit Matters at treefruit.wsu.edu and a link to the original article.