by Helmut Riedl, originally published 1993; revised 2017 by Elizabeth Beers

Dasyneura pyri Bouché (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae)

The pear leafcurling midge is of European origin. It was first detected in New York in 1931 and has since spread to other pear growing areas of North America including the Pacific Northwest. Although pear leafcurling midge has not become a major annual pest in commercial orchards in the Northwest, it can cause concern in nurseries or new plantings. It attacks growing terminals and damages the leaves. On young trees with few terminals it can stunt growth.

Hosts

The pear leafcurling midge is a pest only on pear. A closely related species, the apple leaf curling midge, Dasyneura mali, causes similar leaf damage on apple trees. Pear varieties differ in susceptibility to attack by the pear leafcurling midge. Clapps Favorite, Red Bartlett and Alexander appear to be very susceptible; Anjou, Bosc and Bartlett moderately susceptible; and Conference and Passe Crassane slightly susceptible. Young trees and vigorous older trees with excessive terminal growth are particularly susceptible to attack.

Life stages

Egg

The egg is yellow, elongated and about 1/100 inch (0.3 mm) long. A bright red eye spot appears soon after an egg is laid.

Larva

The small, legless larva is orange at first but later turns white. The mature maggot is 1/12 inch (2 mm) long and develops into a small brown pupa.

Pupa

The pupa is roughly the same size as the mature maggot, and is brown and cylindrical.

Adult

The adult is a gray midge (small fly) and measures 1/25 to 1/12 inch (1 to 2 mm) long.

Life history

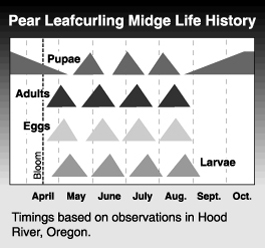

The pear leafcurling midge overwinters as a pupa in the soil. Adults begin to emerge around bloom time and lay eggs on young, still unfolded leaves. Larvae hatch from eggs after 3 to 5 days and feed on leaves. Infested leaves can harbor up to 30 larvae. After feeding within the curled leaves for about two weeks, larvae make exit holes and drop to the ground where they pupate in the top 1 or 2 inches (2-1/2 to 5 cm) of soil. The number of generations in an area depends on seasonal temperature and on the amount of terminal growth, as eggs are laid only on newly developed leaves. There are 4 or 5 generations in most pear growing areas of the Pacific Northwest. On long shoots, infested and healthy leaves alternate, indicating the number of completed generations.

Damage

Damage

Feeding by larvae curls infested leaves. Affected leaves are tightly rolled parallel to the midrib and have red, gall-like swellings. Later, infested leaves turn black and fall. Extensive feeding damage can stunt young trees. It is of less concern on mature trees, where excess vegetative growth is not desirable.

Monitoring

Adult midges appear on developing foliage at bloom time. However, because of their small size they are easily overlooked, especially when their density is low. Yellow sticky boards placed in the tree canopy may be useful for monitoring adults.

Leaves infested by larvae are easily recognized by the characteristic damage symptoms. No treatment thresholds are available for this pest. However, thresholds used for apple aphid on pears can be used for pear leafcurling midge infestations as both pests attack growing terminals.

Biological control

Little is known about natural enemies of the pear leafcurling midge. Leaves curled by the larva provide shelter for generalist predators such as predaceous bugs and ladybird beetles which contribute to biological control of pear psylla and other pests.

Management

This pest is not common, and should not be a consideration in most pest management programs. Where infestations are severe, especially on young trees, control may be considered. The midge can be controlled with postbloom applications of organophosphate insecticides. The first spray should be applied at or shortly after the petal fall stage to control adult midges and young maggots. Subsequent sprays should be timed to coincide with adult emergence and egg laying of later generations.