by Elizabeth H. Beers, Stanley C. Hoyt, and Michael J. Willett, originally published 1993; revised March 2010 E. Beers; and June 2019 Robert J. Orpet.

Eriosoma lanigerum (Hausmann) (Hemiptera: Aphididae)

This aphid, native to North America, was identified in the United States in 1842. It is now distributed throughout the apple growing regions of the world where its importance as a pest varies. The woolly apple aphid may occur on the above-ground portions or roots of the apple tree. Aphid forms inhabiting above-ground parts of the apple tree are most common in mid-summer and fall. The aerial colonies can be found in several locations on the tree, but shoots and watersprouts are favored locations. Overwintering colonies are usually found in old pruning scars, although some survival has been recorded on shoot galls from the previous year’s infestation. The aphids are covered with long white waxy filaments which give the colony a woolly appearance.

Hosts

The original primary (or overwintering) host of the woolly apple aphid is American elm. In areas where this species of elm occurs, elm is the overwintering host, and apple is one of several summer (or alternate) hosts. Winged females dispersing to elm give live birth to wingless males and females. These in turn mate and the females lay eggs which overwinter on elm. However, woolly apple aphid has adapted to live and reproduce asexually on apple year-round in most fruit growing areas of the world (where the American elm does not occur), including the western United States. There is evidence that sexual reproduction occurs on apple in New Zealand, but the importance of this has not been established. Other alternate hosts include hawthorn, mountain ash, and cotoneaster.

Life stages

Egg

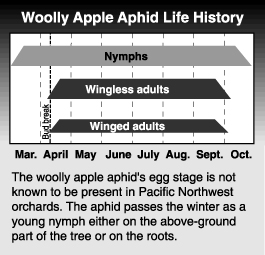

The egg stage is not known to occur in Pacific Northwest orchards.

Nymph

Shortly after birth, the nymph is salmon colored and lacks the woolly coating. This stage is known as the crawler. The waxy filaments begin to form after the aphid settles to feed. There are four nymphal instars, averaging 0.64, 0.67, 1.2, and 1.3 mm in length. Eyes are dark brown to black (no oceli). The cornicles are circular, and only slightly elevated from the surface of the abdomen.

Adult

The adult is reddish-brown to purple. The actual color, however, is usually concealed beneath a white, cotton-like substance secreted from the aphid’s abdomen. This characteristic makes this aphid species easy to distinguish from other aphid species occurring on apple.

Life history

Woolly apple aphid overwinters as a nymph on the roots of apple. It can also overwinter as a young nymph on the above-ground part of the tree in protected areas on the trunk or main limbs. In severe winters above-ground colonies may be killed.

As temperatures warm in the spring, overwintering aphids produce live young that migrate up and down the tree. Nymphs on the roots move upward to provide a source of infestation if above-ground colonies do not survive the winter. Preferred feeding sites during the summer are leaf axils on terminal shoots. When populations are high, most leaves on a terminal will have a cottony mass at the base.

Winged adults (alates) are normally the form that would migrate back to the overwintering host (elm) in the fall. Winged forms have been noted in colonies of woolly apple aphid in the fall in Washington orchards, although their fate is uncertain. There is a persistent speculation that the winged forms may form part of the dispersal mechanism to other apple trees, but the meager evidence on this subject indicates that egg production on apple is rare, and the eggs fail to hatch.

Damage

Galls, or swollen enlargements, form on the plant where aphid colonies feed on twigs or roots. These are not very noticeable after one year of feeding but increase in size as feeding continues in an area. Subterranean aphid colonies cause the most damage. Roots of infested trees have large, abnormal swellings. Continued feeding can kill roots and cause reduced growth or even death of young trees.

The Malling-Merton series of rootstocks (e.g., MM.106 and MM.111) were developed to be resistant to woolly apple aphid, as was the Merton 793 selection, which is commonly used in the southern hemisphere. This resistance is based on a scion cultivar, ‘Northern Spy’. Some rootstocks in a newer series developed by the Geneva rootstock breeding program are resistant to woolly apple aphid (e.g., G.41, G.213, G214, G.22, G.202, G.969, G.210, and G.890). The resistance is based on Malus robusta apple rootstock, and apparently confers a higher level of resistance than the older Malling-Merton series.

Woolly apple aphids are attracted to sunken areas caused by the disease perennial canker. Galls caused by feeding of aphids are re-infection sites for the causal fungus of perennial canker, Cryptosporiopsis perennans. These galls are more sensitive to low temperatures than normal bark tissue and rupture at about 0ºF or colder, providing an entry site for the fungus, continuing the perennial nature of the canker.

Honeydew produced by the woolly apple aphid can drip onto the fruit resulting in sooty mold and downgrading of fruit because of blackened or russeted areas. High populations of woolly apple aphid can create sticky and unpleasant working conditions for harvest crews. Woolly apple aphid can also infest the stem and calyx end of the apples; the presence of live (or even dead) aphids in packed apples is a potential quarantine issue. In some instances, especially varieties with an open calyx, aphids can also infest the apple core.

Monitoring

No specific monitoring procedures or treatment thresholds have been developed for woolly apple aphid. Generally, monitoring should begin in midsummer or perhaps earlier if the winter was mild. If many colonies are in the fruiting zone of the tree, treatment will probably be needed.

Biological control

The parasitoid Aphelinus mali is generally given the most credit for biological control of woolly apple aphid. Although A. mali play a role, research in Washington has shown that a complex of generalist predators including lady beetles, syrphid fly larvae, green lacewings, Deraeocoris brevis, and European earwig is also important. Whereas A. mali leaves behind evidence of parasitism in the form of mummies, the important role of predators can be overlooked because they consume all or part of the colony, leaving no trace of their activities. The more sedentary predators (syrphid larvae) are the easiest to find in aphid colonies; however, more mobile predators also have an impact, and nocturnal predators such as the European earwig may go unnoticed. The latter is considered an important predator of woolly apple aphid in Washington and worldwide. (For more information on specific natural enemies, see Predators or Parasitoids on the Beneficials page).

Management

The pest status of woolly apple aphid in the Pacific Northwest has varied over time. During the era predominated by organophosphate use, it was not considered a serious pest, or at least one that was easily controlled. The transition of pest management programs away from organophosphates has been associated with an increase in the incidence and severity of woolly apple aphid outbreaks. While the causes for this can only be speculative, reducing the use of specific organophosphates in the delayed-dormant and mid-late summer (2nd generation codling moth) are plausible explanations. Organophosphates have been replaced by other groups of pesticides (including IGRs, neonicotinoids, and other novel modes of action), which have little or no toxicity to woolly apple aphid, but may be equally toxic to its natural enemies. In addition, milder winters may improve overwintering survival, and contribute to earlier or higher populations.

Disruption of biological control may be effected to a greater or lesser degree by various pesticides; toxicity of various orchards pesticides to natural enemies has been rated and can be found in the Orchard Pesticide Effects on Natural Enemies Database (OPENED) and within the WSU Decision Aid System App. Recent research and industry experience has indicated that outbreaks are consistently associated with the use of certain codling moth materials such as Rimon (novaluron) and Delegate (spinetoram).

Chemical controls can be applied either proactively or reactively. The use of an organophosphate plus oil in the delayed dormant period has been shown to provide season-long control in some cases, or at least suppression throughout the summer. An effective pesticide can be applied at any time during the season when populations increase. Care must be taken to anticipate a fall outbreak and ensure that the preharvest interval of the pesticide is observed. See the Crop Protection Guide (CPG) for appropriate pesticide choices and timings. An excerpt from the CPG is shown below.

The role of resistant rootstocks is not well understood. The resistant Malling-Merton series presumably mitigated the effect of aphid infestation of the rootstock, but its effect on aerial colony development is unknown. The same should be true of the Geneva rootstocks. It has been stated that interrupting the movement of crawlers from the root colonies to the aerial parts of the tree should prevent the formation of aerial colonies, but preliminary research has shown that this is not the case, at least in small plots; either overwintering survival on aerial portion of the tree, or reinfestation from nearby trees may be responsible.

Woolly Apple Aphid Gallery

Materials Available at Delayed Dormant for WAA (and other aphid eggs) Control in Apple

Materials Available at Post-bloom through Summer for WAA Control in Apple

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

Use pesticides with care. Apply them only to plants, animals, or sites listed on the labels. When mixing and applying pesticides, follow all label precautions to protect yourself and others around you. It is a violation of the law to disregard label directions. If pesticides are spilled on skin or clothing, remove clothing and wash skin thoroughly. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

YOU ARE REQUIRED BY LAW TO FOLLOW THE LABEL. It is a legal document. Always read the label before using any pesticide. You, the grower, are responsible for safe pesticide use. Trade (brand) names are provided for your reference only. No discrimination is intended, and other pesticides with the same active ingredient may be suitable. No endorsement is implied.

References

Baker, A. C. 1915. The woolly apple aphid. Rept. No. 101, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC.

Beers, E. H., S. D. Cockfield, and L. Gontijo. 2010. Seasonal phenology of woolly apple aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in Central Washington. Environ. Entomol. 39:(2):286-294. DOI: 10.1603/EN09280.

Cummins, J. N., P. L. Forsline, and J. D. Mackenzie. 1981. Woolly apple aphid (Eriosoma lanigerum) colonization on Malus cultivars. J. Amer. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 106: 26-30.

Hoyt, S. C., and H. F. Madsen. 1960. Dispersal behavior of the first instar nymphs of the woolly apple aphid. Hilgardia. 30: 267-299.

Patch, E. M. 1912. Elm leaf curl and woolly apple aphid. Bull. 203, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, Orono, ME.

Robinson, T., H. Aldwinckle, G. Fazio, and T. Holleran. 2003. The Geneva series of apple rootstocks from Cornell: performance, disease resistance and commercialization. Acta Hortic. 622: 512-520.

Sandanayaka, W. R. M., and V. G. M. Bus. 2005. Evidence of sexual reproduction of woolly apple aphid, Eriosoma lanigerum, in New Zealand. Journal of Insect Science. 5:27.

Walker, J. T. S. 1985. The influence of temperature and natural enemies on population development of woolly apple aphid, Eriosoma lanigerum (Hausmann). Ph.D. Thesis, Washington State University, Pullman.

Articles from the Tree Fruit website may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Reprint articles with permission must include: Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension Fruit Matters at treefruit.wsu.edu and a link to the original article.