Written by: Claudia Probst and Gary Grove, WSU Plant Pathology; Compiled by: Tianna Dupont, WSU NCW Regional Specialist; Reviewed by: Catherine Danials, WSU Entomology and Pesticide Coordinator; Edited by: Wendy Jones, WSU Tree Fruit Extension. Download PDF

Powdery mildew of sweet and sour cherry is caused by Podosphaera clandestina, an obligate biotrophic fungus. Mid- and late-season sweet cherry (Prunus avium) cultivars are commonly affected, rendering them unmarketable due to the covering of white fungal growth on the cherry surface (Fig. 1). Season long disease control of both leaves and fruit is critical to minimize overall disease pressure in the orchard and consequently to protect developing fruit from accumulating spores on their surfaces.

Identification

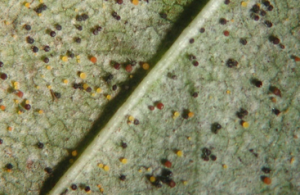

Initial symptoms, often occurring 7 to 10 days after the onset of the first irrigation, are light roughly-circular, powdery looking patches on young, susceptible leaves (newly unfolded, and light green expanding leaves). Older leaves develop an age-related (ontogenic) resistance to powdery mildew and are naturally more resistant to infection than younger leaves. Look for early leaf infections on root suckers, the interior of the canopy or the crotch of the tree where humidity is high. In contrast to other fungi, powdery mildews do not need free water to germinate but germination and fungal growth are favored by high humidity (Grove & Boal, 1991a). The disease is more likely to initiate on the undersides (abaxial) of leaves (Fig. 2) but will occur on both sides at later stages. As the season progresses and infection is spread by wind, leaves may become distorted, curling upward. Severe infections may cause leaves to pucker and twist. Newly developed leaves on new shoots become progressively smaller, are often pale and may be distorted.

Early fruit infections are difficult to identify and you will need a hand lens to identify the start of fungal growth in the area where the stem connects to the fruit (cherry ‘bowl’; Fig. 3).

Lifecycle clues to management

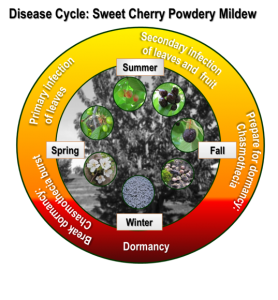

In the fall, P. clandestina produces chasmothecia1 (Fig. 4), small and hardened overwintering structures that harbor ascospores, to lie dormant on senescent leaves or in tree crotches (Grove & Boal, 1991b). In the spring, during a wetness event, such as the onset of irrigation, chasmothecia break open and tiny spores called ascospores (sexual spores) are released which give rise to the first infections of the year, called primary infection. Spores are disseminated by the wind and re-infect young leaves resulting in secondary infections. While ascospores initiate a disease epidemic, (asexual) spores produced during secondary infections are the cause of an area-wide powdery mildew epidemic. By early fall the fungus prepares again for the pending defoliation of its host and consequently enters its overwintering period by the production of chasmothecia. A detailed description of the powdery mildew life cycle can be found in the review article by Glawe (2008) and shown in figure 5.

1 Formerly called cleistothecium

When is mildew active?

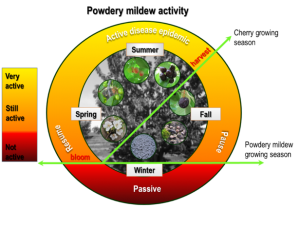

It is important to know when cherry powdery mildew is active because often growers only manage the disease during the cherry fruit growing season. Continue management during the full fungal growing season which continues through late summer and early fall (Fig. 6).

What conditions initiate infection?

Typically, it takes 1/10th of an inch of rain or irrigation and temperatures of 50°F or more for spring primary infections to occur (Grove and Boal, 1991a).

What conditions favor disease?

The fungus does not need free water to thrive. High humidity and temperatures of 70°F to 80°F favor the disease. Spore dispersal is diurnal, with spore concentrations peaking late morning to early afternoon (Grove 1998, Glawe 2008).

Warm temperatures without rain, but with sufficiently high humidity for morning fog or dews, are ideal for a rapid increase of the disease.

Cultural controls

Manage irrigation. In the arid west in a typical dry spring, early irrigation may stimulate early cherry powdery mildew infections. For example, in 2002 Dr. Gary Grove documented the initiation of cherry powdery mildew infections in relationship to spring irrigation. Initial symptoms appeared 7-10 days after the first irrigation of the season in all five orchards monitored. Generally, the ground is still moist in spring and early irrigation may only jumpstart your powdery mildew season versus help your trees. Recent research has shown that a two-week delay in irrigation delayed disease initiation two weeks with no negative impact on fruit.

Pruning. Humid conditions favor cherry powdery mildew. A well pruned canopy will promote more air flow and leaf drying, reducing these humid conditions favorable for disease. Pruning will also help to achieve good spray coverage.

Root sucker management. Root suckers are a preferred by powdery mildews since they are comprised of highly susceptible leaf tissue. Root suckers are close to the irrigation and high humidity levels favor the onset and spread of infections. Additionally, sprays aimed at the canopy often do not protect root suckers allowing fungal inocula to survive all season. Remove root suckers to eliminate this source for infection of the canopy and fruit.

The effect of training system, rootstock, and cultivar on sweet cherry powdery mildew foliar infections has been described by Jill Calabro (2009).

Chemical controls

The key to managing powdery mildew on the fruit is to keep the disease off of the leaves. Most synthetic fungicides are preventative, not eradicative, so be pro-active about disease prevention. Maintain a consistent program from shuck fall through harvest. Consider post-harvest preventative measures (e.g. application of sulfur, prevent trees from pushing for leaf growth) to obstruct the fungus from overwintering (Fig. 6). Preharvest fungicide applications should be based on the residual period of the product. Rotate between modes of action (MOA) in order to avoid resistance (Table 1). Also, visit the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee web page for updated fungicide information and download the fungicide mode of action poster.

Table 1. Materials available for cherry powdery mildew control.

Excerpt from the WSU Crop Protection Guide. For timings at which each pesticide can be used refer to the Crop Protection Guide.

d = dormant; dd= delayed dormant; pp= prepink/pink; b = bloom; pb = post bloom; sf = shuck fall; es = early summer (14-32 after full bloom); s = summer; ls = late summer; ph = preharvest; h = harvest; ah = after harvest

Resistance management

The FRAC code represents the mode of action of the fungicide. Multiple applications of a fungicide(s) with the same FRAC code increases the risk that resistance will develop. Premix fungicides with two modes of action can improve disease control if there is field resistance to one of the active ingredients and help prevent resistance if there is not. Group 11 fungicides, important for cherry powdery mildew, are high risk for resistance development. It is important for resistance management to use cultural practices to reduce disease pressure. Apply fungicides in a protective rather than reactive manner. Limit the number of applications of a single mode of action both during the season and in sequence (rotate between colors, Figure 7). Apply medium risk compounds no more than three times per season and no more than twice in sequence. High risk compounds should always be alternated with other modes of action. Apply high risk compounds to no more than 30% of the total sprays you use in a single season. Tank mixing with sulfur (or other low risk compounds) can also help limit resistance risk.

Additional resources

- Cherry Powdery Mildew Questions and Answers, Gary Grove, Claudia Probst, Tianna DuPont, Dec 2017.

- Cherry powdery mildew: Expect the unexpected, Claudia Probst, Gary Grove, WSU video, January 2015.

- Cherry powdery mildew management guidelines, WSU-DAS article, web page, 2013.

- AgWeatherNet, model status & recommendations for Cherry powdery mildew, web page.

- Mildew threatens cherries all season, M. Hansen, Good Fruit Grower, February 2015.

- WSU Cherry Powdery Mildew Information Network, Facebook.

- Fungicide Resistance Action Committee, web page.

- Rosaceae Nemesis: Cherry Powdery Mildew, RosBreed Newsletter, December 2016.

References

Calabro, Jill Marie, Robert A. Spotts, and Gary G. Grove. 2009. Effect of training system, rootstock, and cultivar on sweet cherry powdery mildew foliar infections.” HortScience 44.2: 481-482.

Glawe, Dean A. 2008. The powdery mildews: a review of the world’s most familiar (yet poorly known) plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46: 27-51.

Grove, Gary G. 1998. Meteorological factors affecting airborne conidia concentrations and the latent period of Podosphaera clandestina on sweet cherry. Plant disease 82.7 (1998): 741-746.

Grove, Gary G., and Robin J. Boal. 1991a. Overwinter survival of Podosphaera clandestina in eastern Washington. Phytopathology 81.4: 385-391.

Grove, Gary G., and R. J. Boal. 1991b. Powdery mildew of sweet cherry: Influence of temperature and wetness duration on release and germination of ascospores of Podosphaera clandestina. Phytopathology 81.10: 1271-1275

Long, L. Cherry Powdery Mildew Control. Oregon State University Extension.

Ogawa, J.M., Zehr, E.I., Bird, G.W., Ritchie, D.F., Uriu, K., and Uyemoto, J.K. 1996. Compendium of Stone Fruit Diseases. St. Paul, MN: APS Press. ISBN: 978-0-89054-174-6.

Author contacts:

Gary Grove

WSU Plant Pathology

Professor & Director

Prosser R&E Center (IAREC)

(509) 786-9283

grove@wsu.edu

Use pesticides with care. Apply them only to plants, animals, or sites listed on the labels. When mixing and applying pesticides, follow all label precautions to protect yourself and others around you. It is a violation of the law to disregard label directions. If pesticides are spilled on skin or clothing, remove clothing and wash skin thoroughly. Store pesticides in their original containers and keep them out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

YOU ARE REQUIRED BY LAW TO FOLLOW THE LABEL. It is a legal document. Always read the label before using any pesticide. You, the grower, are responsible for safe pesticide use. Trade (brand) names are provided for your reference only. No discrimination is intended, and other pesticides with the same active ingredient may be suitable. No endorsement is implied.

Treefruit.wsu.edu articles may only be republished with prior author permission © Washington State University. Republished articles with permission must include: “Originally published by Washington State Tree Fruit Extension Fruit Matters at treefruit.wsu.edu” along with author(s) name, and a link to the original article.